Simplifying Caregiver Resources in Eldercare: Identifying the Support Needs of Caregiving Employees

James S. Powers 1, 2, * ![]() , Barbara Clinton 3

, Barbara Clinton 3 ![]() , Kayse Martin 3

, Kayse Martin 3 ![]() , Margaret A. Genendlis 1

, Margaret A. Genendlis 1 ![]() , Grace S. Smith 3

, Grace S. Smith 3 ![]()

- Center for Quality in Aging, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, USA

- The Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, USA

- The Council on Aging of Middle Tennessee, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, USA

* Correspondence: James S. Powers ![]()

Academic Editor: Lisa A. Hollis-Sawyer

Special Issue: Models of Caregiver Support

Received: October 26, 2018 | Accepted: December 03, 2018 | Published: December 13, 2018

OBM Geriatrics 2018, Volume 2, Issue 4 doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1804024

Recommended citation: Powers JS, Clinton B, Martin K, Genendlis MA, Smith GS. Simplifying Caregiver Resources in Eldercare: Identifying the Support Needs of Caregiving Employees. OBM Geriatrics 2018;2(4):024; doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1804024.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

Background: The majority of long-term care provided to older adults and persons with disabilities is provided by unpaid family caregivers and friends. Employers have a stake in long-term care services as well since 60% of caregivers are employed outside the home, 49% have gone in late, left early, or taken time off during the day to deal with caregiving issues, and 15% have taken a prolonged leave of absence. Additionally, 87% of employed caregivers make telephone calls for caregiving from work. Presenteeism, the state of being on-the-job, but because of caregiving not fully functioning, can greatly reduce individual productivity. Caregivers emphasize the need for information to assist in their tasks with the major barriers to utilization of caregiver resources identified as lack of awareness of available services, challenges accessing community services, and understanding eligibility criteria.

Context: Roobrik is an online decision support tool which uses questions about caregiver and dependent characteristics to help identify caregiver needs, matching these to appropriate types of services. The Council on Aging of Middle Tennessee’s (COA) Directory of Services provides a comprehensive online community resource guide. The human resources department of four Nashville-based employers previously supportive of COA’s work were contacted and agreed to provide information to employees experiencing caregiver concerns. Volunteer employed caregivers willing to utilize the Roobrik Tool and the COA directory and contribute to a focus group discussion were invited to participate.

Methods: Four focus groups were held including a total of 19 participants. Responses were recorded by an experienced journalist. In the Analysis, Phase I, primary themes were categorized by the focus group leader according to questions posed to the participants. In Phase II, secondary themes were developed by expert consensus following review of individual responses by three investigators guided by categories of the 2015 National Alliance for Caregiving’s National Caregiver Survey.

Results: Caregivers spent less than 15 minutes to research and determine the most appropriate local care options. Half of caregivers contacted later planned to act on these recommendations. Based on focus group questions, primary themes were identified: 1) utilization of automated decision support tools, 2) how decision support tools help caregivers understand the caregiver role, 3) ways to improve decision support tool function, and 4) recommendations for improvement of decision support resources. Based on the content of specific caregiver responses, these secondary themes were identified: 1) information needs-medical, legal, quality of life, and the processes involved in obtaining services, 2) needs for specific community support services, 3) need for informal and professional emotional support to reduce caregiver stress, and 4) ways the workplace can support employed caregivers. Workplace policies including flexible time, caregiver support groups, and working remotely may be beneficial to caregivers as well as the workplace.

Conclusions: Our experience implementing a demonstration of the Roobrik tool coupled with the COA Directory of Services suggests these may be useful and accessible online resources to help simplify care navigation and enhance individualized support for caregivers. Some caregiver needs are beyond the capability of online decision support and may require personal guidance.

Keywords

Caregiving employees; community resources; geriatric care

1. Introduction

The majority of long-term care provided to older adults and persons with disabilities is provided by unpaid family caregivers and friends (approximately 85%). The 2015 National Caregiver Survey [1] conducted by the National Alliance for Caregiving in partnership with the American Association of Retired Persons estimated that 43.5 million unpaid caregivers provide assistance to at least one adult and the average caregiver spends over 24 hours per week in this role. Almost 22% of caregivers report their health to be worse because of caregiving strain, 60% of caregivers are women, and 20% take care of two or more people, and only 53% report another unpaid caregiver assists them in their tasks. Major dependent needs include old age 14%, and memory problems 26%, and long-term physical conditions are present in 59%. Some 59% of caregivers help loved ones with at least one activity of daily living: transfers 43%, and personal care tasks including dressing 32%, bathing 26%, toileting 27%, incontinence care 16%, and feeding 23%. They also assisted with an average of 4.2 of 7 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL): transportation 78%, housework 72%, grocery shopping 76%, and other IADL’s including meal preparation 66%, managing finances 54%, and arranging or supervising outside services 31%. The burden of care for caregivers is rated 40% high burden, 18% moderate burden, and 41% relatively low burden, with financial strain increasing with higher burdened caregivers. The Institute of Medicine’s 2008 report, Retooling for an Aging America, Building the Health Care Workforce [2] predicts that the future professional workforce will be inadequate to meet the care needs for our aging population and that we will continue to rely on informal caregiving to supply the majority of long-term care services.

Employers have a stake in long-term care services as well since 60% of caregivers are employed outside the home, 49% have gone in late, left early, or taken time off during the day to deal with caregiving issues, and 15% have taken a prolonged leave of absence from work. Additionally, 87% of employed caregivers make telephone calls for caregiving from work [3]. Presentism, the state of being on-the-job, but because of caregiving not fully functioning, can greatly reduce individual productivity.

Some 78% of caregivers emphasize the need for information to assist in their tasks with the top sources of information identified as healthcare provider 36% and the internet 25%. Half of caregivers utilize technology in the care of the recipient including: electronic organizers and calendars 24%, emergency response systems 12%, devices that sense and send information electronically to medical providers 11%, and other electronic sensors or wandering devices in the home 9% [1].

The major barrier to utilization of caregiver resources continues to be lack of awareness of available services with many caregivers also facing significant challenges trying to access community services, understanding eligibility criteria, and completing applications for services [4]. Making good decisions about long-term care services requires an effective means of learning about the options. Enhanced caregiver sites and interactive tools are potential solutions to caregiving burdens. Tools that are easy to use, that are consistent with the older adult and families’ values, steer caregivers and their dependents to critical questions, and offer options and solutions for their concerns have the potential to enhance the older adults’ comfort and quality of life, facilitate connectedness, and decrease family burden.

Electronic databases make it easier to update and search for services. Examples include the Veterans Administration Geriatrics and Extended Care website [5] with over 40,000 visits per month nationally and 1,000 visits by caregivers and dependents in the Middle Tennessee area, with over 50% of visits comprised of caregivers seeking home and community-based services, and the Council on Aging of Middle Tennessee’s (COA) Directory of Services [6], a comprehensive online directory with brief descriptions updated yearly since 1986.

The Roobrik tool “Is It Time to Get Help?” [7] was launched in October 2016 and is an online decision support tool which uses questions about caregiver and dependent characteristics to help identify caregiver needs, matching these to appropriate types of services in the community. It is designed to help families determine their care needs and which options are the best fit for their caregiving situation. The tool provides a Care Fit Report which lists specific recommendations based on caregiver input. The ability to go online discreetly and quickly obtain guidance on appropriate care options is invaluable as caregivers often feel overwhelmed and the need for care is typically an urgent decision. There is no fee associated for use of this decision support tool and other Roobrik modules are available for issues like dementia, driving and home safety.

We report our experience implementing a demonstration of the Roobrik: Is It Time to Get Help? tool coupled with the COA online Directory of Services as useful and accessible caregiver tools for researching and determining the most appropriate care options.

2. Methods

2.1 Context: Subjects and Setting

The human resources department of four Nashville-based employers previously supportive of COA’s work were contacted and agreed to provide information to employees experiencing caregiver concerns. Volunteer caregivers willing to utilize the Roobrik: Is It Time to Get Help? tool and contribute to a focus group discussion were invited to participate. All were asked to first use Roobrik and the time it took them to complete the task was recorded.

2.2 Focus Groups

Employees who were currently the person providing care to their senior relatives were invited by their employer to a one-hour lunchtime discussion facilitated by masters prepared social worker with expertise in focus groups (BC). Responses and comments were recorded by an experienced journalist (KM). The purpose of the focus group discussions was to elicit information about the decision support tool and the accompanying directory of services, and to identify additional caregiver needs. All participants brought a mobile device, laptop, or tablet to the discussions. All of the participants were full-time adult employees of the work place in which the focus group was held and were caregivers or soon to be caregivers. The moderator began each session with an introduction to encourage a comfortable environment for sharing thoughts and experiences within the group and insured that all participants had an opportunity to speak throughout the session.

Four focus groups were conducted, one for each participating employer. A total of 19 participants were included with a range of 4-7 participants in each focus group. All caregivers were employed middle-aged individuals and included 14 women, five men; six black, and 13 white participants. All subjects provided written informed consent and were given a boxed lunch for their participation. The focus group facilitator guided each session and assisted participants using personal devices (laptops, phones, and tablets) to respond to the following questions about the user experience with the online tool, ease of use, time required, and whether they utilized the COA directory from the Roobrik Care Fit report:

- How would you describe your experience using Roobrik? (Prompts: Was it enjoyable, frustrating? Did it take too long or was the time needed just about right?)

- What did the tool provide that was helpful? (Prompt: Did it tell you anything, or trigger anything that was surprising?

- What did you want from the tool that it didn’t give you?

- What about the tool was not helpful? (Prompts: Did you find it difficult to use? Was using the tool disturbing or unsettling in any way?)

- What would you do to improve the tool? (Prompt: What information is still needed?)

- After you reviewed your report, if you clicked on the link to use the COA online directory to find local resources, was it clear how to find community resources?

- If you didn’t use the directory, why not?

- What else would be helpful to you as a working caregiver?

Figure 1 shows a sample Care Fit report with recommendations based on caregiver input.

Caregivers can utilize the Roobrik tool as often as desired or needed to create new reports.

Figure 1 Care Fit Report. Reproduced with permission of Cigna-HealthSpring® and Roobrik®

A follow up call was made 2-3 weeks following the focus group to all participants (repeated for a total of 3 attempts), who were asked the following questions:

- Did you act upon information received in the Care Fit report when you used Roobrik? (If yes, what did you do? What was your experience? If no, please explain why not?)

- From the Care Fit report, did you click the link to use the COA online directory to find local resources? (If so, what was your experience with the directory?)

- What would you do to improve the online tool?

This project was supported by the CTSA award no. ULITR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The Roobrik subscription for the Council on Aging was provided by an unrestricted sponsorship from Cigna-HealthSpring.

The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved this project.

3. Results

3.1 Analysis, Phase I: Development of Themes- Using an Online Decision Support Tool to Identify Caregiving Resources: Primary Themes

Focus group responses from 19 participants were recorded by an experienced journalist and primary themes categorized by the focus group leader according to questions posed to the participants.

3.1.1 Use of the Automated Decision Support Tool

All participants moved through the tool easily. The tool took each participant approximately 15 minutes to complete, including setting up a personal profile and consulting the directory.

- Participants described the tool as easy to use and the appropriate length

- Participants commented that the tool was user friendly, not frustrating, and flowed very easily. One participant said “I liked being able to start right away, without doing a lot of reading”

- Several whose caregiving situations had stabilized expressed that they wished they had had access to such a tool at an earlier stage of caretaking

3.1.2 How the Decision Support Tool Helped to Understand the Caregiver Role

Participants mentioned that the questions helped them clarify their caregiving roles, both comprehensively as well as in embracing the many details they manage or will manage as caretakers. There were positive comments about the tool’s coverage of many problems that caregivers face, and the tool’s suggestions of a wide range of responses. Several participants noted that the tool reminded them to seek out the perspectives of the person being cared for. Specific comments included:

- I liked getting a better understanding my needs and then looking at other needs

- ;The tool made me think of things that I don’t normally think about

- I liked the experience of figuring out my situation

- The tool helped me visualize a plan of care

- I’m glad that there were questions related to Veteran’s benefits

- Including words like “sometimes” made it easier to answer questions in a situation where my senior’s needs are constantly changing

- The tool helped me realize that I should think more about my relative’s wishes

- The tool helped me realize the information I should draw out in conversations with my mother-in-law

- I liked getting a report I could take with me

- The questions helped me see that my mother in law is actually in good shape, but her situation could change in the blink of an eye and we have to be ready

- The options that were presented made me think of even more options

3.1.3 Ways to Improve the Decision Support Tool Function

There were two negative opinions

- The way the tool works is not giving you the best answers

- It gave me the answers I thought it would

Several participants suggested re-designing the tool so that it can be used collaboratively with others so that family members can compare answers and generate a more comprehensive picture for the individual being cared for. Other suggestions for improving the tool included:

- Add questions about the age of my family member

- Add questions about who else is helping my family member

- Add more questions or information related to the legalities of caregiving like power of attorney and conservatorship

- Add a “progress indicator” at top of page to show how far I’ve proceeded in completing the tool

- Ask if any member of the family’s workplace has an EAP that can help

- The tool did not seem linear; the questions did not seem to follow a logical line. I would have liked categories like social, medical, etc.

- Add the option of “NA” or “not applicable” to each question

Participants who commented on dementia suggested making the questions more detailed and specific, to allow the caregiver access to a finer understanding of the loved one’s needs and resources.

- Dementia is multi-faceted and changes with the passing of time, I wanted more detailed responses to the dementia questions.

- My loved one did not exactly fit the current questions, although dementia is an issue for her

- After I clicked “yes” on dementia, I wanted a breakout of the stages so I could identify where she is in the disease process

- The dementia responses are not finely detailed enough, did not fit my mother although I think she has dementia

- Similar symptoms can be caused by many diagnoses, and different services may be needed based on diagnosis

- Would like more specific diagnoses and options that define the problems. What about personality disorders, etc.?

3.1.4 Recommendations for Improvement of Decision-Support Resources

Most participants responded favorably to the amount and kind of information provided by the directory. Those who used the directory said it was clear in its explanations of how to find the resources but requested more clarity in the definitions of services and how to pay for them. Other suggestions for improvement included adding information about how services are vetted and licensed, especially for services that take place in the home. In addition, more information on how to manage the cost of services was requested by several participants.

Add information on how to evaluate services

- A list of questions to ask when visiting a service provider would be good

- What should I be looking for?

- I wanted more information on how services are vetted or licensed, especially those that would come into my home

- I’d like to be able to read reviews of the services, like it’s possible to do on Amazon

- Consumer Reports types ratings of services would be good

Add information on how to cover the cost of services

- Add an overview of senior financial issues, and how to plan and manage paying for services

- Better and more complete information on financial resources is needed

- Not knowing how to pay for services is a huge source of stress

Help finding services in other areas & show where the services are

- The directory only lists local services. My parents live out of state, I need to access services and resources where they live

- Need information on services in neighboring counties

- Include a map so I can see where services are in my county, and in relation to other services

Improve linkage/access to the directory & features, ease of use

- I had trouble finding the directory. Make it easier to access the directory, put additional directions on the last page of Roobrik

- It took a lot of time to investigate each provider

- The search was too broad, wish it could have been narrowed down

- I wish I could save the work I’ve done on it, so I can go back to it next time

- The right side of page could be used to help clarify definitions

- If you know what services you need, it’s easy to use

3.2 Analysis, Phase II: Development of Secondary Themes:

Secondary themes were developed by expert consensus following review of individual responses by three investigators (JP, JS, GS) following discussion of categories of the 2015 National Alliance for Caregiving’s National Caregiver (NAC) Survey.

As caregivers at various stages of the caregiving experience, participants described a variety of their unmet needs which impact the quality of the care they can provide. Participants were generous in providing ideas that might make their caregiving easier and more successful and for the senior they care for. The discussions of caregivers’ needs fell into four categories: 1) the need for caregiver information, 2) the need for emotional support for both caregivers and seniors, 3) the need for community assistance to supplement family care, and 4) ways that employers can be helpful to employed caregivers.

3.2.1 Information Needs

The largest category of unmet needs fell within the information category. There were many areas of caregiving where caregivers feel unprepared to do the job well and to make wise decisions. Caregivers expressed the need for fact sheets and training sessions about how to make the home space safe and how to manage the loved one’s diet and meals. Caregivers also expressed a desire to become knowledgeable and skillful in more complex aspects of caregiving including how to manage and talk about the end of life and hospice care, and how to recognize and adapt to disabilities as they arise and change as part of the process of getting older. One participant explained that she was completely unaware that there was any help to access information about services.

Medical information - Participants expressed the desire for more information for making medical care decisions, including

- Help with understanding what happens when my mother is at the doctor, and I am not with her

- As the end of life approaches, I need to know when to stop bringing my older person to the doctor, which is adding stress to the dying person. The doctor never tells you this

- I need to know how to talk about end of life issues before it’s the end of life

- Need more outreach and information about end of life and hospice care, from hospice staff

- Need help with the hospice transition

- More general information and training about disabilities and getting older, maybe from the senior center or church

- My senior has several diagnoses; I don’t know which services she needs for which diagnosis

Legal information

- There are several types of POA (power of attorney). How do I know which one we need?

- Could the forms needed for POA and other transactions be printed from the directory?

- How do I get conservatorship?

- A “clinic” on a Saturday, offering information on legal and other questions would be helpful

Information to help the senior live well at home

- Help with knowing how to make the home space safe

- Help knowing how to manage my loved one’s diet and meals

- Information on how to protect my elderly father from harassment

- Help with financial planning so that my senior can stay in her own home and remain independent on the income she has

- I need information on how to help my senior’s life be enriched

- Transportation is a huge issue for us

- Help with my senior’s personal security. I’ve told her not to answer the door but she takes too many online quizzes and buys things online that she doesn’t need

Organizational information and assistance

- Help keeping track of doctors, medications, and pharmacy, especially for parents who are out of state

- We need help triaging the mail. What is accurate, what is a come on? What is a priority, what is actionable?

- I would like help understanding the unfamiliar. I feel overwhelmed with banking, insurance, Medicare, paying bills

3.2.2 Need for Specific Community Support Services to Supplement Family Care

Even the most advantaged and committed caregivers recognize that doing the job alone is not an effective strategy. Assistance from someone else, whether on a daily or occasional basis, can make caregiving easier for the caregiver, and better for the person being cared for. Specific ways that outside help could be used were suggested in the groups, including:

- A consultant to give you orientation and help you get organized when you are new at caregiving

- I need consultation and/or counseling services

- I need a person to convince my mother to get the help she needs

- I need a liaison between me and my parent to help bridge the gap in communication about care

- I need an “Ambassador” to help my senior understand that accepting services does not put her at financial risk

- Information presented at a senior center or church would be better accepted by seniors

- It would be great to have someone who could do a home visit from time to time, to make a brief check in on my mom

- I need occasional access to a lawyer and financial advisor, Medicare is a mystery

- I need someone to call for information and referrals to community resources

- We need an “Ask the Caregiver” hotline that I can call when I’m at work, and/or someone that my parent can call with a question

- We need activities for my senior, to relieve his boredom

- I need enough knowledge so that I am not stressed because I don’t feel prepared for what is going to happen next

3.2.3 Need for Emotional Support to Reduce the Stress of Caregiving

Caregiving for a senior, even when it is going well, can exhaust the caregivers’ energy, morale, finances, and tolerance for stress. Overwhelmed by the many losses that both the senior and the caregiver experience through the process of aging, both parties can find themselves operating at less than optimum level. Caregivers’ ability to find the emotional support they need helps them maintain the stamina and commitment they need to do the job well. Participants described many specific ways that they need emotional support to be effective in the caregiving role, for instance:

- Help dealing with anger and losing my patience. Even though you know it’s not your fault, you end up raising your voice

- It unnerves me when my aunt calls me and is confused. It weighs heavy on me, I am a worrier

- Emotionally it is very hard. My heart is in one place, with my parent, but my mind is in another, with work

- I need to know how to talk about end of life issues before it’s the end of life

- My mom had a stroke at 50. I wonder how long I will have to care for her

- When I see my aunt, I think that my daughters are going to be doing this with me in 30 years

- Dealing with the dynamics of other involved family members is very hard

- I try to remember “One day at a time, one situation at a time”

- I need affordable mental health services for me while I go through this

- I need someone who understands. I know all of these things are available if you have money - but I don’t

- I’m just on the verge of caregiving and I’m already frustrated with it. Our parents push our buttons, just the way our kids do

- I need to know how to de-escalate the emotions in conversations with a person with Alzheimer’s

- I need help managing when my mom calls me at work. It’s hard to know if it’s a crisis or not. My mother cannot discern what is a crisis

- My parent is stubborn (or tough, manipulator, persuasive). I need help communicating effectively with her/him

Securing professionally guided emotional support

Participants specifically mentioned the options of support groups of other caregivers, or individual counseling as good ways to find the emotional support they need. Making use of these opportunities when they are available, is difficult for employed caregivers whose time is already being consumed on the job, or in the caregiving role. In addition, several caregivers mentioned that there is a stigma to seeking mental health treatment.

- I need support groups, so I can talk with other caregivers

- I need a group but cannot attend and still do everything else I am expected to do

- In support groups, it would be good to have a member of the group (not the leader of the group) with clinical experience, to answer questions and serve as a resource on meds, etc.

- I need a chat room, where I can go with questions as they come up

- I need a meet up group or a support group, because I have no “me” time

- I wish we had support groups at work, at lunch time. I don’t have time to attend anything in the evening, because I’m caregiving

- Faith communities could provide mental health support on site, to make a safe (non-stigmatized) place

- I need consultation and/or counseling services

3.2.4 Ways that the Workplace Can Support Employed Caregivers – Workplace Policies

- We need more caregiver friendly workplace policies - flexible schedules, paid time off, the ability to work remotely. These things currently depend on the personality of the immediate supervisor. They should be rights for good workers

- Flex time and the option to occasionally work at home would be enormously helpful

- I’m the HR guy, I know we have services through the employee assistance program (EAP) but I haven’t used them. We need to publicize what is available right here [at our workplace and create greater awareness of the services available through EAP

- It is great when employers let you use sick time for taking care of your parent’s needs

- The workplace leadership culture needs to support caregivers

- In our stores it is probably harder to support caregivers than in the main office, because in the stores we need our folks on duty at all times. We should talk with the field managers about how they can support caregivers who work in the stores

3.3 Phase III: Post Focus Group Data

Performance metrics for traffic through the COA website at baseline (for 3 months prior to the focus group, January to March 2018) and 3 months after the focus groups were conducted (April to June 2018) showed increased utilization of the tool and time spent on the site, with decreased time to complete use of the tool. There was also increased number of individuals using the tool, and opting-in, sharing contact information with COA. (Table 1)

Four individuals who participated in the focus groups were able to be contacted (21%) and two (50%) reported that they were acting on recommendations obtained from the decision support tool’s Care Fit report.

Table 1 Performance Metrics-Council on Aging (COA) Website Page with Link to Roobrik Tool

|

|

Baseline |

Post focus group |

Change % |

|

Number of users to the landing page |

70 |

98 |

40 |

|

Average time on the site (minutes) |

5:39 |

6:17 |

11.2 |

|

Number who stay on the site |

48 |

57 |

18.8 |

|

Number completing the tool |

29 |

46 |

58.6 |

|

Average time on the site (minutes) |

13:12 |

12:36 |

(4.7) |

|

Number opting-in to use tool, sharing contact information with COA |

13 |

30 |

130.7 |

4. Discussion

Subjects readily utilized the Roobrik: Is It Time to Get Help? tool and provided numerous recommendations regarding improvement of the tool and resources for caregivers including consultation lines, chat rooms, and information regarding finances and advance care planning.

Caregivers were clear in their recommendations to transform the COA Directory of Services from a catalog of services to a guide providing direction on important subjects including definitions of different services, a primer on financing health and care services, and guidance on how to choose service providers.

In addition, caregivers provided a wealth of information on specific categories of need. In discussions related to their roles as caregivers, participants identified needs in three areas: 1) general information related to aging and caregiving, 2) assistance in organizing the many demands of the caregiving role, and 3) support in managing the emotional stress triggered by the caregiving process. Secondary themes included 61 responses which were reduced to four categories, informed by the 2015 national caregiving survey: 1) detailed information on medical, legal, quality of life at home, cost of care, and the processes involved in obtaining services; 2) community support services to supplement family care, 3) emotional support, both informal and professional, to reduce caregiver stress, and 4) workplace support for employed caregivers.

The goal of caregiver information support tools and websites is to increase the capacity of caregivers to make informed choices about long-term care services consistent with their values and the needs of their dependents. Provision of virtual care management and care coordination services through the use of self – directed technology provides a personalized single point of care and a virtual “professional partner” to better support family caregivers and the patients they represent. All caregivers successfully created profiles based on their needs. Half of caregivers contacted planned to act on these recommendations. For caregivers who are internet-savvy, decision support services may aid in accessing resources. This is in contrast to the experiences of disadvantaged populations, as suggested in the Tennessee 2017 Comptroller’s Report, where lack of a single point of entry for services means that older Tennesseans seeking community assistance experience difficulty utilizing lists of resources and subsequently do not follow-up and complete applications for publicly-supported services [4].

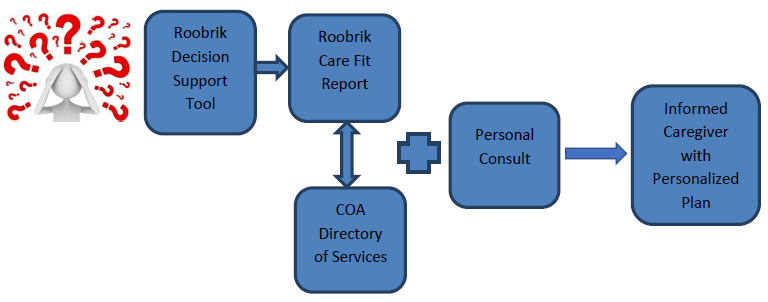

There is a great amount of information needed by caregivers including availability and costs of services, eligibility criteria, and how to choose service providers. Many secondary themes were expressed, based on individual caregiver needs, and these corroborate the results of the 2015 NAC Survey. Our participants expressed a great interest in guidance for end-of-life care and decision-making, as requested by 22% of caregivers in the 2015 NAC Survey. Automated decision-support may not be able to provide for all needs, especially for dementia caregivers, and supplemental personal caregiver support and counseling may be necessary to address individual needs. We have developed a caregiver optimization schema based on feedback from caregiver subjects’ requests for supplemental support and counseling to better personalize caregiving recommendations. (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Caregiver Optimization Flow Diagram. Caregivers utilize the Roobrik: Is It Time to Get Help? Decision support tool via the Council on Aging website to generate an individualized Care Fit Report of recommendations based on caregiver input. Caregivers then utilize COA’s online Directory of Services to locate community resources and services in Middle Tennessee, and can call the COA office for an Information/Referral consult.

The NAC Survey reports that among higher-burdened employed caregivers, 76% of supervisors are aware of caregiver giving demands. Among full-time employees, 53% report availability of flexible hours, 52% report availability of paid sick days, 23% report employee assistance programs, and 22% report availability of telecommuting for work. Additionally, a British study found that among older workers age 50-75 years, women who indicated a caregiving role greater than 10 hours per week were between 2.64 and 4.65 times more likely to exit the work force [8].

4.1 Barriers–Limitations

The results from this focus group survey are limited to the small number of employed middle-aged caregivers included, but corroborate findings from the 2015 NAC Survey. Only 21% of focus group participants participated in the follow-up survey concerning intention to utilize information from the Care Fit report. Older and disadvantaged caregivers, and those caring for special-needs dependents may have different support needs.

4.2 Implications–Conclusions

Online virtual care navigation and management services are readily utilized by educated caregivers. These end-users provide insight into improvements of the tools and can help identify additional resource needs to enhance and individualize support for caregivers. Many services may be available only in larger metropolitan areas so self – directed virtual care management may be limited by local availability of services. Inclusion of wider service networks may offer a more enriched plan of care for the caregivers and other family members, facilitating long-distance caregiving. Creation of caregiver information sites to share best practices may support caregivers and stimulate development of a new generation of virtual care management tools and referral help lines.

Combining information services and professional recommendations and referrals based on eligibility and needs also makes available an array of patient care needs across the skilled and nonskilled continuum. Based on our focus group responses, COA plans to pilot a "care coach consult" service where caregivers can pre-schedule a 30-minute phone consult with a qualified professional for care navigation assistance.

Employers have the potential to be useful partners in supporting caregivers. Their involvement in support of employed caregivers may benefit families as well as the workplace. Some caregiver needs such as professional caregiver support to cope with stress, are beyond the capabilities of automated decision support tools and require personal consultation and guidance.

Acknowledgments

John Schnelle PhD, Vanderbilt Center for Quality Aging, for review of focus group questions and an early version of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

James S. Powers, Grace S. Smith: concept design, analysis, manuscript preparation; Barbara Clinton: focus group leadership; Kayse Martin: focus group transcription and data collection; Margaret A. Genendlis: concept design.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- National Alliance for Caregiving, National Caregiver Survey. Caregiving in the United States, 2015 https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2018)

- Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America. Building the Health Care Workforce (2008) https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12089/retooling-for-an-aging-america-building-the-health-care-workforce (Accessed May 17, 2018)

- National Alliance for Caregiving, National Caregiver Survey. Caregiving in the United States, 2009 http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2018)

- Tennessee Comptroller’s Report: Office of Research and Accountability. Senior Long Term Care in Tennessee, Trends and Options. 2014 http://www.comptroller.tn.gov/Repository/RE/aging.pdf (Accessed May 28, 2018)

- Department of Veterans Affairs, Geriatrics and Extended Care Website https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/ (Accessed May 11, 2018)

- Council on Aging of Middle Tennessee. Senior Services Directory http://www.coamidtn.org/directory/ (Accessed May 28, 2018)

- Roobrik online decision support tool “Is It Time to Get Help. https://tools.roobrik.com/home/care/start (Accessed May 28, 2018)

- Carr E, Murray ET, Zanonotto P, Cadar D, Head J, Stansfeld S, et al. The association between informal caregiving and exit from employment among older workers: Prospective findings from the UK household longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Sci. 2018; 73: 1253–1262.