The Four-Facet Model of Eudaimonic Resilience and Its Relationships with Mindfulness, Perceived Stress and Resilience

Fraser L. E. Fisher 1, †, *![]() , Aileen M. Pidgeon 1, †

, Aileen M. Pidgeon 1, †![]()

- Bond University, 14 University Drive, Gold Coast, Australia

† These authors contributed equally to this work.

* Correspondence: Fraser L. E. Fisher![]()

Received: July 10, 2018 | Accepted: August 13, 2018 | Published: August 27, 2018

OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018, Volume 3, Issue 3 doi:10.21926/obm.icm.1803015

Academic Editors: Sok cheon Pak, Soo Liang Ooi

Special Issue: Health Benefits of Meditation

Recommended citation: Fisher FLE, Pidgeon AM. The Four-Facet Model of Eudaimonic Resilience and Its Relationships with Mindfulness, Perceived Stress and Resilience. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018; 3(3): 015; doi:10.21926/obm.icm.1803015.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

Elevated levels of psychological distress in university students is a growing area of concern as it is associated with a variety of consequences including mental illness symptoms, absenteeism, and poor academic performance. A growing body of research has indicated that resilience in university students is associated with reduced psychological distress and perceived stress. The construct of resilience and the factors that contribute to its development are not well understood, hampering the development of effective interventions. Key factors including mindfulness (paying attention on purpose and non-judgementally in the present moment), positive reappraisal (reframing perceived stress as meaningful), positive emotion, and reduced psychological distress are associated with fostering resilience in the face of perceived stress. These four factors are termed eudaimonic resilience. The present study examined whether perceived stress, mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress accounted for variance in university student resilience (N = 164). A theoretical framework of eudaimonic resilience development was examined with mediation. Hierarchical regression indicated that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress predicted variance in resilience over and above that of perceived stress. Additionally, mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress significantly mediated the relationship between perceived stress and resilience. Increased mindfulness, positive emotion, and positive reappraisal predicted increased resilience, while increased psychological distress predicted decreased resilience. These results provided preliminary support for a theoretical framework of eudaimonic resilience development and informed resilience interventions. Limitations and future research are discussed.

Keywords

Resilience; eudaimonic; positive reappraisal; mindfulness; university students

1. Introduction

University students have been found to be exposed to greater risk of psychological distress and mental health problems compared to age-matched peers [1]. Increased psychological distress in university students is associated with decreased quality of life, mental health problems, and poorer academic performance [2]. Stallman [3] reported a significantly higher proportion of university students reported very high levels of distress relative to the age-matched general population. The elevated psychological distress was associated with significantly reduced academic performance as well as absenteeism [3]. Tung, Ning, and Kris [4] reported that increased levels of perceived stress in tertiary students were associated with increased levels of psychological distress. High levels of resilience have been proposed to assist with the major life transition to the elevated stress of the university environment [5]. Increased levels of resilience have been found to be associated with reduced perceived stress and reduced psychological distress [4]. Thus, understanding the relationship between perceived stress and resilience is an important step in addressing psychological distress in university students. The construct of resilience is not well understood and increased understanding of the factors that predict resilience is warranted to inform the development of interventions [6].

Bauer and Park [7] theorized the term eudaimonic resilience refers to regulation of affect as well as meaning-making when faced with perceived stress. Bauer and Park [7] postulated affect regulation involves the ability to regulate positive and negative emotions while meaning-making included the capacity to positively reappraise the meaning associated with an aversive life event. Garland, Farb, Goldin, and Frederickson [8] proposed the mindfulness-to-meaning theory which postulates that mindfulness facilitates meaning-making in the form of positive reappraisal of perceived stress as well as affect regulation in the form of increased positive emotion and reduced psychological distress. Under this theoretical framework, eudaimonic resilience is comprised of four factors: mindfulness, positive reappraisal, increased positive affect, and reduced psychological distress. When confronted with perceived stress, the upward spiral of these four factors may lead to the development of resilience. Alternatively, perceived stress may trigger a downward spiral of these four factors leading an individual to be less resilient to future perceived stress. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the mediating role of the four factors of eudaimonic resilience (mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress) in the relationship between perceived stress and resilience.

1.1 Resilience

Resilience has been defined as the ability to negotiate, adapt to, or manage significant stressors [22]. The benefits of resilience have been increasingly investigated over the past two decades as resilience focuses on promoting healthy development in contrast to previous deficit models that focused on managing illness and psychopathology [22]. To create a theoretical framework to assist with the identification of potential factors related to the development of resilience, Bauer and Park [7] postulated that eudaimonic resilience is a process involving affect regulation (regulating positive and negative emotions) and meaning-making (positively reappraising the meaning of perceived stress) that contributes to the development of resilience.

Ryff [24] argued that previous conceptualizations of resilience have focused on social support while providing less attention to meaning-making as an essential process for developing resilience. Additionally, Garland et al. [8] theorized that positive reappraisal of perceived stress and positive emotions foster the generation of meaning and resilience. Thus, previous theories have proposed that eudaimonic resilience is a process focused around an individual’s ability to make meaning of perceived stress as well as increasing positive emotions and decreasing negative emotions to develop resilience. This process was theorized to promote an upward spiral of emotion regulation and meaning-making that is associated with increased resilience [8]. Previous research has found significant positive relationships between resilience, mindfulness, and positive emotions supporting this theoretical framework [19].

1.2 Mindfulness

Mindfulness has been defined as actively paying attention in the present moment to the unfolding of experience without judgement [14]. Being open to and non-judgemental of experiences and events may lead to adaptive functioning as maladaptive thoughts and feelings can be recognised and managed to reduce distress [14]. Mindfulness has been proposed to increase awareness of cognitive and emotional processes that may contribute to psychological distress while facilitating adaptive responses to these processes [15]. Previous research has supported this theory and found mindfulness to be highly correlated with reduced psychological distress [16]. Mindfulness has been shown to be positively related to resilience which has been considered an adaptive response to life stressors [19]. Previous research has reported mindfulness as a significant predictor of resilience [20]. Additionally, individuals with high levels of resilience have reported significantly lower levels of psychological distress and significantly higher levels of mindfulness relative to individuals with low levels of resilience [21]. Consequently, the findings from previous research indicate a predictive relationship between mindfulness and resilience which is related to reduced levels of perceived stress and psychological distress. Past research has not examined the predictive relationships between mindfulness, resilience, perceived stress, and psychological distress to understand how all these variables are related.

1.3 Integrating Eudaimonic Resilience and Mindfulness

Garland, Gaylord, and Park [28] stated that mindfulness assists with coping with adverse life situations by promoting positive reappraisal of perceived stress. Positive reappraisal is an active, meaning-based cognitive coping strategy that involves reframing perceived stressors as neutral, meaningful, or growth-inducing [27]. Garland et al., [28] reported that positive reappraisal mediated the relationship between perceived stress and mindfulness. Further research reported that mindfulness and positive reappraisal reciprocally enhance one another while reducing perceived stress [29]. Additionally, positive reappraisal has previously been linked with reduced psychological distress [26]. Positive reappraisal and mindfulness interventions have been demonstrated to increase positive emotion in university students [29].

Garland et al. [31] proposed the mindfulness-to-meaning theory to conceptualize how mindfulness fosters positive reappraisal of perceived stress leading to meaning-making and eudaimonic responses to stress. Making meaning of perceived stress with positive reappraisal leads to positive emotion which promotes increased eudaimonic responses to future perceived stressors [31]. When a stressor is perceived, mindfulness attenuates negative attentional biases and maladaptive behaviours creating cognitive space for the positive reappraisal of the perceived stress. These factors combine to promote meaning-making and regulation of positive emotion and psychological distress when confronted with perceived stress, promoting the development of eudaimonic resilience. The conceptualization put forward by Garland et al. [31] fits under the dual-process of affect regulation and meaning-making outlined by Bauer and Park [7].

According to these two theories, the development of resilience in the face of perceived stress is mediated by meaning-making in the form of mindfulness and positive reappraisal as well as affect regulation in the form of positive emotion, and psychological distress. Previous research has partially supported this theoretical framework. Palmer and Rodger [33] reported that perceived stress was a significant negative predictor of mindfulness in university students. Additionally, Alemi, James, Siddiq, and Montgomery [34] reported that levels of perceived stress predicted levels of psychological distress in refugees. Previous research has further reported inverse relationships between perceived stress with positive emotion and positive reappraisal [25,35]. Significant negative relationships have been found between psychological distress and resilience [11]. Keye and Pidgeon [20] reported that mindfulness in Australian university students predicted levels of resilience. Positive reappraisal has been found to positively predict levels of resilience in depression and anxiety outpatients [36]. Additionally, high levels of positive emotion have been found to predict levels of resilience in a longitudinal study of police officers [37].

1.4 Psychological Distress and Perceived Stress in University Students

Stallman’s [3] study with 6,479 Australian university students found that 83.9% of the sample reported elevated levels of psychological distress. Additionally, 19.2% had levels of psychological distress indicative of probable serious mental illness, while 64.7% displayed subsyndromal symptoms of probable mild to moderate mental illness and only 16.1% were classified as non-cases. Contrary to the 19.2% of university students that reported very high levels of distress, 3% of the age-matched peer group in the general population indicated comparable distress levels. The elevated levels of psychological distress in university students were associated with significantly lower academic performance. Additionally, increased psychological distress was related to an increase in the number of days where students felt unable to work, study, and manage daily activities [3]. Thus, Australian university students are at high risk for mental illness, elevated levels of psychological distress, and impaired functioning highlighting the need for increased understanding of the underlying mechanisms of psychological distress and identification of protective factors that may help reduce psychological distress. According to Garland, Farb, Goldin, and Frederickson [8] transactional model of stress and coping (TM), individuals perceive a situation as stressful based on whether they have adequate available coping resources to deal with the stressor. Understanding how students perceive academic stressors and the mechanisms underlying potential coping resources is important to assist in effectively managing perceived stress and associated psychological distress. Investigation of the four-facet model of eudaimonic resilience in university students may provide insight into the predictive relationships between perceived stress, resilience, mindfulness, and psychological distress.

Previous research has provided partial support for eudaimonic resilience in university students. Resilience has been found to be inversely related to perceived stress in university students [9]. Tung et al. [4] supported these results and found that increased resilience was correlated with reduced perceived stress in university students. Additionally, increased perceived stress was related to increased psychological distress while increased resilience was related to decreased psychological distress [4]. Shilpa [23] supported these results and reported a significant negative relationship between resilience and perceived stress in a different university sample. Shapiro, Oman, Thoresen, Plante, and Flinders [17] found that increased levels of mindfulness in undergraduate students were related to reduced levels of perceived stress. Additionally, increased mindfulness has been found to be significantly related to reduced psychological distress and fewer psychological symptoms in university students [18]. High levels of mindfulness have shown to be related to lower levels of psychological distress in Australian university students [10] Previous research with Australian university students has reported mindfulness as a significant predictor of resilience [20]. Additionally, Australian university students with high levels of resilience have reported significantly lower levels of psychological distress and significantly higher levels of mindfulness relative to Australian university students with low levels of resilience [21]. Pidgeon and Keye [11] further supported the association between mindfulness and resilience in Australian university students. Harker, Pidgeon, Klassen, and King [12] reported associations between higher levels of both mindfulness and resilience with lower levels of psychological distress. Furthermore, mindfulness has been reported to be inversely related to perceived stress [13]. However, previous research has not examined the predictive relationships between perceived stress, resilience, mindfulness, and psychological distress in Australian university students within the theoretical framework of the four-facet model of eudaimonic resilience.

1.5 The Current Study

The present study aimed to examine the relationship between perceived stress and resilience in university students.

Hypothesis 1: It was predicted that perceived stress would significantly predict levels of resilience. Additionally, it was predicted that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress would significantly account for variance in resilience over and above that accounted for by perceived stress.

Hypothesis 2: It was predicted that the criterion variable perceived academic stress would have significant predictive relationships with the mediating variables: mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive affect, and psychological distress.

Hypothesis 3: It was predicted that the mediator variables mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress would demonstrate significant predictive relationships with resilience.

Hypothesis 4: It was hypothesized that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive affect, and psychological distress would significantly mediate the relationship between perceived academic stress and resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants in the current study were 164 Australian university students consisting of 47 males (28.7%) and 117 females (71.3%) with ages ranging from 18 to 54 years old. Inclusion criteria included being currently enrolled at an Australian university, being over 18 years of age, and speaking English.

Ethics approval for the study was provided by the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee under code 0000015629.

2.2 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; [38])

Participants were asked to complete the CD-RISC [38], a 25-item self-report measure designed to assess the ability to thrive in the face of adversity as well as evaluate the strength of stress-related coping skills. The CD-RISC was chosen for the present study as it has been found to be a reliable and well-validated measure of resilience in the general population [39]. Higher scores on the measure indicated greater resilience. Examples of the statements presented include “I am unable to adapt when changes occur” and “I can deal with whatever comes my way”. The CD-RISC has been found to have good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of .89 [38]. The present study found a comparable Cronbach’s alpha of .90.

2.3 Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; [40])

Participants were asked to complete the DASS-21 [40] which was designed as a 21-item measure of psychological distress using three subscales including the individual severity of depression, anxiety, and stress. The DASS-21 was used for the present study as it has been found to be a valid measure of depression, anxiety, and stress as well as overall psychological distress [41]. Higher scores indicated increased levels of psychological distress. Henry and Crawford [41] reported an excellent Cronbach’s alpha of .93. The present study found a comparable reliability coefficient of .93.

2.4 Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; [42])

The PANAS is a 20-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess the comparative levels of individuals’ levels of positive and negative affect. Participants were presented with single-word emotional descriptors and instructed to indicate the extent to which each descriptor applied to how they felt over the previous week. The measure consists of two subscales to measure both positive and negative affect separately with higher scores indicating higher levels of positive or negative affect. The positive affect subscale was used for the present study. Crawford and Henry [43] reported good reliability for the positive affect scale with a Cronbahch’s alpha of .89. The present study found a comparable Cronbach’s alpha of .90 for positive affect.

2.5 Perceptions of Academic Stress Scale (PAS; [44])

The PAS was designed to measure perceptions of academic stress among university students with an 18-item self-report questionnaire. The PAS has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of perceived stress for university students [44]. Higher scores indicate increased levels of perceived academic stress. The PAS was reported to demonstrate adequate internal consistency (α = .70) [44]. The present study supported the internal consistency of the PAS with a Cronbach’s alpha of .82.

2.6 Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; [45])

The SCS is a 26-item self-report measure designed to tap self-compassion that is comprised of six subscales including: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. The SCS was chosen for the present study as it was developed using a sample of university students recruited through a participation pool similar to the current study [45]. Higher scores indicated increased levels of self-compassion. The current study utilized the mindfulness subscale. Neff [45] reported adequate internal consistency for the mindfulness subscale with a Cronbach’s alpha of .75. The present study found a similar internal consistency for the mindfulness subscale (α = .70).

2.7 Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; [46])

The CERQ is a 36 item self-report questionnaire designed to measure the cognitive coping styles employed by an individual following an aversive event. The CERQ has been found to be a reliable and valid measure in an adult general population sample making it an acceptable measure of positive reappraisal in the current study [46]. The present study used the positive reappraisal subscale. Garnefski & Krajj [32] demonstrated adequate reliability for each subscale with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .75 to .86. The present study supported the internal consistency of the positive reappraisal subscale with a Cronbach’s alpha of .91.

3. Results

Statistical analyses in the present study included data diagnostics, preliminary correlational analyses, hierarchical multiple regression, and multiple mediated regression. Data diagnostics were first run to assess whether the data violated any assumptions of regression analyses. Pearson’s product-moment correlations were then run to analyse the bivariate relationships between the study variables. Hierarchical multiple regression was then run to determine whether variance in the criterion variable resilience could be accounted for by the predictor variables (perceived stress, mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, psychological distress). The predictor variables were entered into the regression equation in two steps with perceived stress added at Step One and mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress added at Step Two. The order of entry was determined by the mindfulness-to-meaning theory which stated that the four variables added at Step Two are the most important factors for predicting resilience [31]. A multiple mediated regression was then run to examine the predictive relationships between the study variables with perceived stress set as the predictor variable, resilience set as the criterion variable, and four mediating variables including mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion and psychological distress. All statistics were conducted using SPSS version 24. An alpha level of p = .05 was used to assess significance in all tests.

3.1 Preliminary Analysis

Prior to the main analysis, Pearson’s correlations were run to examine the relationships between the study variables. Uncentred means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Uncentered Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations of Resilience, Perceived Stress, Mindfulness, Positive Reappraisal, Positive Emotion, and Psychological Distress.

3.2 Hierarchical Multiple Regression

A hierarchical multiple regression was run to investigate whether the predictor variables accounted for significant variance in the criterion variable. The mindfulness to meaning theory proposed that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress are the important variables when predicting resilience [31]. Thus, perceived stress was added at Step One to control for its effects, and mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress were added at Step Two. With the addition of all the predictor variables, the overall model was found to account for a significant amount of the variance in resilience, R2 = .54, adjusted R2 = .53, F(5, 158) = 37.50, p < .001. These findings indicated that the overall regression model accounted for over half of the variance in resilience. With the inclusion of perceived stress to the model at Step One, the model was found to account for a significant additional 18% of the variance in resilience, R2change = .18, Fchange(1, 162) = 36.33, p < .001. Perceived stress was found to be a significant negative predictor of resilience such that increased levels of perceived stress predicted reduced levels of resilience. For every 1.00 SD increase in perceived stress there was a related 0.43 SD decrease in resilience. Mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress were then added at Step Two while controlling for perceived stress. The model was found to account for an additional 36% of the variance in resilience, R2change = .36, Fchange(4, 158) = 31.05, p < .001. Mindfulness was found to be a significant positive predictor of resilience indicating that increased scores on mindfulness predicted increased scores on resilience. For every 1.00 SD increase in mindfulness there was an associated 0.15 SD increase in resilience. Positive reappraisal was also found to be a significant positive predictor of resilience such that increased levels of positive reappraisal predicted increased levels of resilience. For a 1.00 SD increase in positive reappraisal there was an associated 0.22 SD increase in resilience. Additionally, positive emotion was a significant positive predictor of resilience indicating that increased scores on positive emotion predicted increased resilience levels. Increases of 1.00 SD in positive emotion were related to 0.32 SD increases in resilience. Psychological distress was observed to be a significant negative predictor of resilience. Increased scores on psychological distress predicted reduced scores on resilience. Every 1.00 SD increase in psychological distress was associated with a 0.25 SD decrease in resilience. Perceived stress was no longer a significant predictor of resilience at this final step.

Table 2 Hierarchical Multiple Regression Predicting Resilience from Perceived Stress at Step One, and Mindfulness, Positive Reappraisal, Positive Emotion, and Psychological Distress at Step Two.

3.3 Multiple Mediation Analysis

A multiple mediation analysis was run to investigate whether the mediator variables (mindfulness, positive reappraisal, psychological distress, and positive emotion) mediated the relationship the predictor variable (perceived stress) and the criterion variable (resilience) in university students. Mediation analysis was run using Hayes [47] PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 2.16.3) utilizing 5000 bootstrapped samples. Mediation was demonstrated if the 95% bias corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effects did not include zero as this is the only necessary test of significance to establish mediation according to Hayes [47].

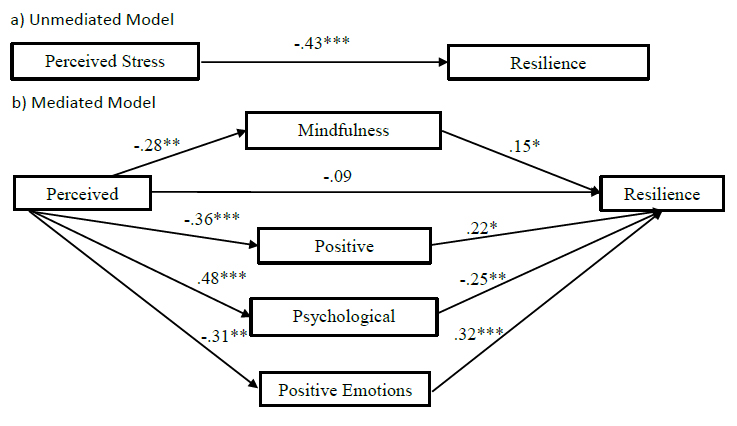

Figure 1 contains a graphical illustration of the unmediated and mediated models with standardized values and levels of significance for each relationship. The unmediated total effect (Path C) was significant such that increased levels of perceived stress predicted decreased levels of resilience. All four relationships between perceived stress and the mediators were found to be significant providing support for Path A. Specifically, perceived stress was found to be a significant negative predictor of mindfulness, positive reappraisal, and positive emotions indicating that increased levels of perceived stress predicted decreased scores on mindfulness, positive reappraisal, and positive emotion. For every 1.00 SD increase in perceived stress there was an associated 0.28 SD decrease in mindfulness, 0.36 SD decrease in positive reappraisal, and 0.31 SD decrease in positive emotion. Perceived stress was further found to be a significant positive predictor of psychological distress such that increased scores on perceived stress were associated with increased psychological distress scores. For every 1.00 SD increase in perceived stress there was a related 0.48 SD increase in psychological distress.

Figure 1 Unmediated and mediated model of the relationship between perceived stress and resilience using mindfulness, positive reappraisal, psychological distress, and positive emotions (*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001).

The mediator variables were further found to have significant predictive relationships with resilience providing support for Path B of the mediation model. All mediating variables were deemed to have complete indirect effects as they had significant Path A relationships with the predictor variable and significant Path B relationships with the criterion variable. Mindfulness, positive reappraisal, and positive emotion were all found to be significant positive predictors of resilience. Increased scores on mindfulness predicted increased scores on resilience. For every 1.00 SD increase in mindfulness there was a related 0.15 SD increase in resilience. Additionally, increased levels of positive reappraisal were predictive of increased levels of resilience. Every 1.00 SD increase in positive reappraisal predicted a 0.22 SD increase in resilience. Higher levels of positive emotion further predicted higher levels of resilience such that 1.00 SD increases in positive emotion were associated with 0.22 SD increases in resilience. Finally, psychological distress was observed as a significant negative predictor of resilience. For every 1.00 SD increase in psychological distress there was an associated 0.25 SD decrease in resilience.

When all the mediator variables were added to the mediated model, the direct effect of perceived stress on resilience (Path C’) was found to be non-significant indicating that the direct effect was reduced in the mediated model relative to the unmediated model. The mediators’ indirect effects were deemed significant if their bootstrapped 95% bias corrected confidence intervals (CIs) did not include zero. Significant indirect effects were found for mindfulness (lower CI = -.11, upper CI = -.00), positive reappraisal (lower CI = -.15, upper CI = -.03), positive emotion (lower CI = -.17, upper CI = -.05), and psychological distress (lower CI = -.20, upper CI = -.06). Furthermore, the total mediation effect of all the combined indirect effects was found to be significant (lower CI = -.48, upper CI = -.23). Pairwise contrasts indicated that there was no significant difference in the strength of any of the indirect effect for the mediating variables when compared to each of the other mediators individually. Overall the results supported the prediction that the relationship between perceived stress and resilience was significantly mediated by mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress.

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the mechanisms underlying the relationship between perceived stress and resilience, as the factors that relate to the development of resilience in the face of perceived stress are poorly understood [6]. To achieve this aim, the present study employed hierarchical regression to examine whether mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress predicted variance in resilience while controlling for perceived stress. To further examine the predictive relationships between the variables, the present study used multiple mediated regression to investigate whether mindfulness, positive emotion, positive reappraisal, and psychological distress mediated the relationship between perceived stress and resilience.

The first hypothesis predicted that perceived stress would significantly predict levels of resilience. Additionally, due to the importance of the four factors of eudaimonic resilience (mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress) in the theoretical framework influenced by the mindfulness-to-meaning-theory [31] and Bauer and Park’s [7] model of eudaimonic resilience, these four factors would account for variance in resilience over and above that accounted for by perceived stress. The results of the hierarchical multiple regression supported the second hypothesis and indicated that perceived stress significantly predicted levels of resilience such that increased perceived stress predicted reduced resilience aligning with previous research [4,9]. Mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress were further found to predict significant variance in resilience over and above that of perceived stress fully supporting the second hypothesis. Mindfulness was found to have a positive predictive relationship with resilience which builds upon previous research that has found a positive association between mindfulness and resilience [11,19].

Previous research has reported that high levels of positive reappraisal predicted high levels of resilience [36]. The present study supported these findings and found positive reappraisal to be a significant positive predictor of resilience. Positive emotion was also found to positively predict levels of resilience aligning with research conducted by Cohn et al. [48] which found that increased levels of positive emotions predicted increased levels of resilience in university students. Finally, psychological distress was found to negatively predict levels of resilience which supports previous research that reported an inverse relationship between the two variables [4]. The results demonstrated that perceived stress significantly predicted levels of resilience until mindfulness, positive reappraisal, psychological distress, and positive emotion were added into the regression model suggesting that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, psychological distress, and positive emotion are the important variables for predicting resilience. These findings supported the predictions of eudaimonic resilience and the mindfulness-to-meaning theory that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress would predict levels of resilience in the face of perceived stress [7,31]. Furthermore, the findings of the hierarchical regression suggested that the variance in resilience predicted by perceived stress is better accounted for by the four variables that make up eudaimonic resilience. However, hierarchical regression does not provide information about the potential predictive pathways that exist between perceived stress and resilience.

The following hypotheses involved further testing the predictive relationships between the predictor variable perceived stress, the criterion variable resilience, and the proposed mediating variables mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress. The second hypothesis was that the predictor variable perceived academic stress would display negative predictive relationships with mindfulness, positive reappraisal, and positive emotion as well as a positive predictive relationship with psychological distress. The results of the present study fully supported this hypothesis. A significant negative predictive relationship was found between perceived stress and mindfulness such that increased levels of perceived stress were found to predict reduced levels of mindfulness. This finding supported previous research in Canadian university students which found that perceived stress was a significant negative predictor of mindfulness [33]. Additionally, perceived stress was found to be a significant positive predictor of psychological distress which aligned with previous research conducted in Afghan refugees and expanded the findings to Australian university students [32]. Increased perceived stress further predicted reduced positive emotion building upon previous research in university students that reported an inverse association between perceived stress and positive emotion. Finally, perceived stress was a negative predictor of positive reappraisal which was consistent with the research of Garland et al. [34]. These findings suggested Australian university students faced with high levels of perceived stress were predicted to employ reduced mindfulness and positive reappraisal while experiencing more psychological distress and less positive emotion.

The third hypothesis predicted that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress would display significant predictive relationships with resilience in the mediated model. In line with previous research with Australian university students, mindfulness was found to have a positive predictive relationship with resilience [20]. Additionally, increased positive reappraisal predicted increased resilience supporting the research of Min et al. [36]. Positive emotion was a positive predictor of resilience which supported previous longitudinal research with police officers that found high levels of positive emotions predicted high levels of resilience over time [37]. Psychological distress negatively predicted levels of resilience building upon previous correlational research in university students [4]. Australian university students that reported high levels of mindfulness, positive reappraisal, and positive emotion as well as low levels of psychological distress were predicted to have increased levels of resilience.

The final hypothesis stated that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress would significantly mediate the relationship between perceived stress and resilience. The results of the present study fully supported the hypothesis and found that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress significantly mediated the relationship between perceived stress and resilience. These results provided support for the process of eudaimonic resilience contributing to the development of resilience in university students faced with perceived stress [7]. Bauer and Park [7] postulated that affect regulation and meaning regulation facilitated the development of resilience when an individual was faced with perceived stress. Combined with the mindfulness-to-meaning theory [31] which theorized that meaning-making of perceived stress involves mindfulness and positive reappraisal while affect regulated involves increased positive emotion and reduced psychological distress. The results of the present mediated model provided preliminary support for this theoretical framework indicating that the four mediators are important variables to consider when developing future interventions aimed at fostering resilience in university students faced with perceived stress.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present study provided novel information related to the factors that predict the development of resilience when university students are confronted by perceived academic stress. These results provided support for the prediction that mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and psychological distress are the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between perceived stress and resilience based upon Bauer and Park’s [7] dual-process model of eudaimonic resilience and the mindfulness-to-meaning theory [31]. When individuals are confronted with perceived stress, they may employ a mindful positive emotion regulatory process that fosters resilience to future adversity. This process is due to the affect regulation provided by increased positive emotion and reduced psychological distress as well as the meaning regulation associated with mindfulness and positive reappraisal. These factors create a positive feedback loop that is related to an overall increase of resilience to recurrent adversity. Therefore, interventions that target the associated factors of mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and positive reappraisal may help university students confront perceived stress with more adaptive responses and foster resilience.

A limitation of the present study was that parallel multiple mediation such as that employed in the current study does not provided information about the causal pathways between the mediators [47]. Future research is needed to examine the exact causal relationships between the four factors of eudaimonic resilience to determine how the process functions. The present study provided initial support for a theoretical framework designed to aid with understanding the development of resilience in the face of perceived stress. Thus, the results of the present study highlighted specific factors that could inform development of interventions for university students struggling with elevated levels of perceived stress. These factors could help Australian university students create an upward spiral of mindfulness, positive reappraisal, positive emotion, and reduced psychological distress when faced with perceived stress that would make them more resilient to future adversity. Future research is needed to expand the present findings and develop and test interventions based upon the novel theoretical framework.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr Aileen Pidgeon for assisting with the development and fine-tuning of this research.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Funding

No funding was provided for this research.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Leahy CM, Peterson RF, Wilson IG, Newbury JW, Tonkin AL, Turnbull D. Distress levels and self-reported treatment rates for medicine, law, psychology and mechanical engineering tertiary students: Cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010; 44: 608-615. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A. Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013; 148: 1-11. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Stallman HM. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Aust Psychol. 2010; 45: 249-257. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Tung KS, Ning WW, Kris L. Effect of resilience on self-perceived stress and experiences on stress symptoms a surveillance report. Univers J Pub Heal. 2014; 2: 64-72. [Google scholar]

- Munro B, Pooley JA. Differences in resilience and university adjustment between school leaver and mature entry university students. Aust Commun Psychol. 2009; 21: 50-61. [Google scholar]

- Leppin AL, Bora PR, Tilburt JC, Gionfriddo MR, Zeballos-Palacios C, Dulohery MM, et al. The efficacy of resiliency training programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9: e111420. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Bauer JJ, Park SW. New frontiers in resilient aging : life-strengths and well-being in late life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012: 60-89. [Google scholar]

- Garland E. The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping. Complem Heal Pract Rev. 2007; 12: 15-30. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Pourafzal F, Seyedfatemi N, Inanloo M, Haghani H. Relationship between Perceived Stress with Resilience among Undergraduate Nursing Students. J Hayat. 2013; 19: 41-52. [Google scholar]

- Slonim J, Kienhuis M, Di Benedetto M, Reece J. The relationships among self-care, dispositional mindfulness, and psychological distress in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2015; 20: 1-13. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Pidgeon AM, Keye M. Relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and pyschological well-being in University students. Int J Liberal Arts Soc Sci. 2014; 2: 27. [Google scholar]

- Harker R, Pidgeon AM, Klaassen F, King S. Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work. 2016; 54: 631-637. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Atanes AC, Andreoni S, Hirayama MS, Montero-Marin J, Barros VV, Ronzani TM, et al. Mindfulness, perceived stress, and subjective well-being: A correlational study in primary care health professionals. BMC Complem Altern M. 2015; 15: 303. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol: Science and Practice. 2003; 10: 144-156. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol: Science and Practice. 2004; 11: 230-241. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Parto M, Besharat MA. Mindfulness, psychological well-being and psychological distress in adolescents: Assessing the mediating variables and mechanisms of autonomy and self-regulation. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2011; 30: 578-582. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Oman D, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, Flinders T. Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. J Clin Psychol. 2008; 64: 840-862. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Bowlin SL, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Personality Individual Differ. 2012; 52: 411-415. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Montero-Marin J, Tops M, Manzanera R, Piva-Demarzo MM, Álvarez de Mon M, García-Campayo J. Mindfulness, resilience, and burnout subtypes in primary care physicians: The possible mediating role of positive and negative affect. Frontiers psychol. 2015; 6: 1895. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Keye M. Pidgeon A. Investigation of the relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and academic self-efficacy. Open J Soc Sci. 2013; 1: 1-4. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- McGillivray CJ, Pidgeon AM. Attributes among university students: A comparative study of psychological distress, sleep disturbances and mindfulness. Eur Sci J. 2015; 11: 33-48. [Google scholar]

- Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2010; 21: 152-169. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Shilpa S, Srimathi NL. Role of Resilience on Perceived Stress among Pre University and Under Graduate Students. Int J Indian Psychol. 2015; 2: 142-149. [Google scholar]

- Ryff CD. Self-realisation and meaning making in the face of adversity: A eudaimonic approach to human resilience. J Psychol Afr. 2014; 24: 1-12. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30: 849-864. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garland E. The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping. Complem Heal Pract Rev. 2007; 12: 15-30. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Lazarus SR, Folkman S. Stress, Ap-praisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google scholar]

- Garland E, Gaylord S, Park J. The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore-NY. 2009; 5: 37-44. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garland E, Gaylord S, Fredrickson B. Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness. 2011; 2: 59-67. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Pogrebtsova E, Craig J, Chris A, O’Shea D, González-Morales MG. Exploring daily affective changes in university students with a mindful positive reappraisal intervention: A daily diary randomized controlled trial. Stress Health. 2018; 34: 46-58. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garland EL, Farb NA, Goldin P, Fredrickson BL. Mindfulness Broadens Awareness and Builds Eudaimonic Meaning: A Process Model of Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation. Psychol Inq. 2015; 26: 293-314. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V. The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric Features and Prospective Relationships with Depression and Anxiety in Adults. Eur J Psychol Ass. 2007; 23: 141-149. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Palmer A, Rodger S. Mindfulness, stress, and coping among university students. Can J Counselling. 2009; 43: 198-212. [Google scholar]

- Alemi Q, James S, Siddiq H, Montgomery S. Correlates and predictors of psychological distress among Afghan refugees in San Diego County. Int J Culture Mental Heal. 2015; 8: 247-288. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Permuth-Levine R. Differences in perceived stress, affect, anxiety, and coping ability among college students in physical education courses (Doctoral dissretation). Ann Arbor: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (3260387); 2007. [Google scholar]

- Min JA, Yu JJ, Lee CU, Chae JH. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies contributing to resilience in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. Compr Psychiat. 2013; 54: 1190-1197. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy I, Brown A, Henn-Haase C, Metzler T, Neylan T, Marmar C, Desteno D. Positive and negative emotion prospectively predict trajectories of resilience and distress among high-exposure police officers. Emotion. 2013; 13: 545-553. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18: 76-82. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Campbell‐Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): Validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. J Traumatic Stress. 2007; 20: 1019-1028. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995. [Google scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2005; 44: 227-239. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54: 1063-1070. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2004; 43: 245-265. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Bedewy D, Gabriel A. Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Heal Psychol Open. 2015; 2: 2055102915596714. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Neff KD. The Development and validation of a scale to measure self- compassion. Self Identity. 2003; 2: 223-250. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality Individual Differ. 2001; 30: 1311-1327. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Methodology in the social sciences). New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google scholar]

- Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL, Brown SL, Mikels JA, Conway AM. Happiness unpacked: Positive Emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion. 2009; 9: 361-368. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]