Complementary and alternative treatment of MS – A study of three cases

- Karolinska Institutet, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Alfred Nobels Allé 23, 141 52 Huddinge, Sweden

* Correspondence: Katarina Mark ![]()

Academic Editor: James D. Adams

Special Issue: Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Nervous System Conditions

Received: June 9, 2018 | Accepted: November 15, 2018 | Published: November 27, 2018

OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018, Volume 3, Issue 4 doi: 10.21926/obm.icm.1804031

Recommended citation: Mark K, Arman M. Complementary and alternative treatment of MS – A study of three cases. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018;3(4):031; doi:10.21926/obm.icm.1804031.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

Background: People suffering from multiple sclerosis (MS) commonly use complementary and alternative medicine due to the partial efficacy of conventional treatments, the chronic aspect of MS, the impact of pain and the side-effects of medication. An exploratory descriptive study of three cases was performed to document and analyse the experience patients treated for MS with applied kinesiology. Methods: Qualitative interviews were conducted with three patients who had been diagnosed with MS at the Neurology Department and who had sought concurrent applied kinesiological treatment from a kinesiologist. The interviews were open-ended and semi-structured. A second interview was conducted for validation. The interviews produced texts that were subjected to phenomenological-hermeneutic text analysis. The three case studies were synthesized for a cross-case analysis. Results: The following themes emerged from the interviews: “having hope”, “trusting the kinesiologist”, “diet changes essential”, “losing trust in the healthcare system”, “feeling confused” and “getting better”. Patients who underwent applied kinesiology treatment reported a sense of hope, trust and increased health. Comprehensive analysis of the survey results revealed that the patients felt able to “make changes for life”, “get past their diagnosis of multiple sclerosis” and “experience increased health” through applied kinesiology treatment. Conclusion: The interviews provide phenomenological-hermeneutic narratives of health well-being among patients treated with applied kinesiology for MS. The treatment assisted the patients in achieving a sense of well-being and health rather than invalidity. In parallel, the patients exhibited stabilization of their magnetic resonance imaging results during the applied kinesiology treatment period. The patients also reported a feeling that they could transcend their diagnosis of MS.

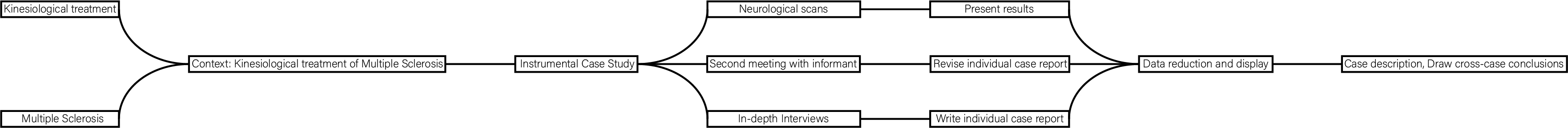

Graphical abstract

Keywords

Complementary and alternative medicine; CAM-treatment; applied kinesiology; case study; multiple sclerosis

1. Introduction

People suffering from multiple sclerosis (MS) commonly use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) due to the partial efficacy of conventional treatment [1], the chronic nature of the condition [2,3], the impact of pain [4], and the side-effects of several medications [5,6]. Here, applied kinesiological treatment of MS was evaluated in an exploratory descriptive study consisting of three cases, as a means of enhancing scientific assessment [7]. Interviews were conducted to describe the personal experiences of patients receiving kinesiological treatment for MS.

2. Background

2.1 Multiple Sclerosis

Autoimmune diseases affect between 5% and 7% of the adult population in Europe and North America [8]. Included among these diseases is MS, an inflammatory demyelinating condition of the central nervous system caused by abnormal immune mechanisms [9]. The resulting injury to the myelin in the central nervous system, and to the nerve fibers themselves, interferes with the transmission of signals between the brain and spinal cord and other parts of the body (National MS Society 2017). The onset is primarily within the age range of 20–40 years and twice as many women are affected compared with the incidence in men [10]. Symptoms may be mild, such as numbness in the limbs, or severe, such as paralysis or loss of vision. The progress, severity, and specific symptoms of MS are unpredictable and vary from one person to another. While the etiology of MS is still unknown, a combination of several factors are thought to be involved. Studies are ongoing in the areas of immunology, epidemiology and genetics to find the cause of the condition. Since MS is more common in northern latitudes and less common in areas closer to the equator, the possible protective effects of increased exposure to the sun and the vitamin D it provides on those living nearer the equator are under investigations. MS occurs in most ethnic groups, including African-Americans, Asians and the Hispanic/Latino population, but is more common in Caucasians of northern European ancestry (National MS Society 2017). Less visible subjective symptoms of pain, fatigue and depression are common and burdensome and adversely affect the patient’s quality of life [11,12,13].

2.2 Multiple Sclerosis and Conventional Medicine (CM)

People with MS can experience one of four disease courses, each of which might be mild, moderate, or severe. A number of disease-modifying agents are currently available, including Avonex and Betaseron (interferon beta [IFN β]-1b), Copaxone®(glatiramer acetate[GA]) and Tysabri (natalizumab), which can reduce disease activity and progression for many individuals with relapsing forms of MS, including those with secondary progressive disease who continue to have relapses [14]. Treatment of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is currently being based on immunomodulatory drugs, such as recombinant IFN β-1a and IFN β-1b) or GA, although these therapies have been shown to be only modestly effective. Recently, it has been suggested that the nerve damage, supported by the inflammatory processes, is an early event in MS evolution, which immunomodulatory drugs can only partially prevent. In clinical trials, IFN and GA demonstrated only partial efficacy that could be ascribed to the fact that the studies that have led to their approval have been initiated in patients with a disease history of several years. Early IFN β-1a treatment has been shown to be effective in preventing the conversion of the first isolated demyelinating episodes into clinically definite MS both after 1 year and 2 years of follow-up. Side-effects and the occurrence of adverse event were the same as those reported in the many studies on IFN β treatments administered to patients with different levels of MS [14,15]. MS damages several parts of the nerves, not only the myelin sheath. GA (Copaxone®) is a synthetic amino acid polymer empirically shown to suppress experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of MS. In this review, we found that the available data do not support a beneficial effect of GA in preventing both disease progression, measured as a sustained worsening in disability, and clinical relapses. With regard to adverse events, no major toxicity was observed, although local injection-site reactions were observed in up to 50% of treated patients [16].

2.3 Multiple Sclerosis and CAM

CAM use is wide spread among patients with MS; 57% to 81 % of patients use CAM at some point during the course of their disease [3,5,7,17,18,19]. An internet search for information using the search words “CAM and MS” rendered 689 000 hits, indicating a vast interest. Many factors influence the utilization of CAM, such as socio-demographic variables of age, aspects of illness, and the severity of MS [7,17]. Common CAM therapies are dietary modification, nutritional and herbal supplementation, mind-body therapies, low-fat diet, and essential fatty acid supplementation [20]. The efficacy of specific vitamin supplementation remains unclear [21]. Recently, cannabis, yoga and meditation have been evaluated in controlled studies that have provided evidence of some benefits [22]. Healthcare professionals require knowledge of CAM therapies, their interactions with conventional treatments, and related research to safely facilitate patients´ exploration and utilization of CAM [23]. Naturopaths use both a multiple, broad-ranging CAM therapies for treating MS and report treatment effectiveness on the following outcomes: quality of life, symptom severity, relapse rates, and disease progression [24]. Increased odds of using CAM in females and the more highly educated individuals have been reported in four studies [25].

2.4 Applied Kinesiology

Applied kinesiology (AK) was first developed in 1964 by the American chiropractor George Goodheart and is now used by chiropractors, osteopaths, medical doctors, dentists and others with a license to practice. Dr. Goodheart found that evaluation of normal and abnormal body function could be accomplished using muscle tests. A body of basic and clinical evidence has been generated on the manual muscle test (MMT) since its first reviewed publication in 1915. Rosner and Cuthbert define AK as a system designed to evaluate structural, chemical and mental aspects of health by MMT together with other methods of diagnosis leading to a variety of non-invasive treatments which involve “joint manipulations or mobilizations, myofascial therapies, cranial techniques, meridian and acupuncture skills, clinical nutrition and dietary management, counseling skills, evaluating environmental irritants, and various reflex techniques” [26]. While performing the kinesiology MMT, the tester is evaluating the patients’ ability to maintain a flexed position in a selected joint. The therapist subjectively monitors the resistance created by the patient against the tester’s pressure or tension. External conditions, such as being in touch with chemical substances, healthy or unhealthy, may increase or decrease this resistance [27]. Single case studies using AK techniques have been performed [28,29], one concerning a boy with ADHD and the other concerning a boy suffering from Lyme disease. Both studies utilized AK as a diagnostic tool. AK can be combined with numerous other CAM treatments and is utilized in many variations.

Holographic kinesiological treatment (HKT) was used by the practicing kinesiologist in this study. HKT is a system developed to strengthen the immune system and combines medical knowledge from areas of neurology, metabolism, anatomy, nutrition, oxygenation, and pH-value and uses the nervous system to identify different weaknesses in the body. Depending on the results - how the body reacts - the therapist treats the client with different techniques, such as nutrition (vitamins and minerals), acupuncture, osteopathy, homeopathy and craniosacral treatments as well as addressing the patient’s thoughts and feelings. When the developers of the system first started using the treatments, they achieved an understanding of how the body works, and to be able to help their clients the practioners had to develop nutrition and supplements of their own brand to make sure it helped every process in the body. Therefore, the treatments include a unique combination of one or several of the following: herbal medication, vitamins, supplements, and dietary and physical training recommendations. The treatments are classified as integrative medicine, meaning that they are both alternative and complementary to conventional medicine. The three cases described here, and particularly Case 3, illustrate that there are no competitive interactions between CM and HKT treatments.

2.5 Health Narratives

Kleinman makes distinctions between the perspectives of the patients and their family´s on the disease. Recognition of the structural or functional perspective and sickness as the macro social perspective is essential for a medical holism [30]. The philosopher Toombs, who suffered from MS from her late twenties, describes in detail the process of the decline of her body resulting in alienation [31] and states that “in health the body is taken for granted and ignored”. She experiences her body as damaged and diseased rather than whole, hindering her ability to live her life. This rift between the body as lived and the biological body, and between the complex perceptions of reality, is also defined by Carel [32] as alienation. Svenaeus goes on to describe illness as an un-home-likeness of being-in-the-world and consequently, health as a home-likeness of being-in-the-world [33].

As a concept, health is defined by the World Health Organization (2017) “ as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. The Cochrane Collaboration defines CAM as “a domain of healing resources… other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture”[34]. In a broader sense, the concept of life vitality, that is itself a holistic term, is more inclusive of individual variations and experiences of health. Holism is central to CAM theories and practices, involving “all aspects of lifestyle, including environment, diet, physical fitness, emotional stability, emotional awareness, sense of faith”[35]. CAM is further defined as complementary: a non-mainstream practice used together with conventional medicine, and alternative: as a non-mainstream practice used in place of conventional medicine (NCCIH, 2016). Integrative medicine is the convergence of conventional and complementary medicine in a coordinated manner [36].

2.6 Problem Area

The etiology of MS is still unknown and patients suffering from MS commonly seek CAM treatments. Due to the scarcity of studies on AK treatment in general and of AK treatment of MS in particular, it is important to conduct an exploratory descriptive case study of patient experiences of AK treatment of MS.

3. Aim

The objective of the case study is to document and analyze the experience of applied kinesiological treatment of patients suffering from multiple sclerosis.

4. Methods

To map out an area that previously has not been the topic of academic research, a qualitative approach is adequate to obtain an overall picture of a new phenomenon, and through interviews, a phenomenon is highlighted, analyzed and described [37,38]. Qualitative methods are useful for the study of human and social experience, communication, thoughts, expectations, meaning and attitudes [38].

4.1 Case Study

We conducted an exploratory descriptive case study into a field that is currently undocumented. This method is suitable for analyzing the etiology and mechanisms of a contemporary subject over which the investigator has little or no control [39]. Furthermore, Yin proposes that a case study can be used to investigate a phenomenon in depth in its real-life context and is especially applicable when the boundaries between a phenomenon and its context are not evident. This is a multi-case study and its strength is the rationalization of literal and theoretical replication, making it more robust than a single case study [39].

4.2 Context

Inclusion criteria: purposive sampling was used to select patients who had been diagnosed with, and treated for, MS at a neurology department in Stockholm and simultaneously and individually sought CAM-treatment from a specific kinesiologist. Exclusion criteria: patients who sought only one form of treatment. The kinesiologist practiced at an AK treatment center outside Stockholm and established in 1995. The number of informants was based on the number of patients referred by the kinesiologist and who agreed to participate in the study. More patients could have been selected, but due to time limitations, the selection process stopped after consent to participate was received from three patients. The case study design rendered the need for more cases superfluous. The treating kinesiologist contacted the patients by telephone during September and October 2016, requested their participation, and following acceptance, forwarded contact information to the first and corresponding author. Two patients declined to participate in the study. According to the kinesiologist, the three patients were selected because they were the first he encountered who met the inclusion criteria of having been diagnosed as suffering from MS by a MD and who also sought AK treatment. The patients had no prior and/or present knowledge of each other. No relationship was established between patients and researchers prior to study commencement. Two separate interviews were conducted, a primary interview and a second follow-up interview performed during October and November 2017.

4.3 Data and Data Collection

The sample comprised three patients who had been diagnosed with MS by a MD and who were receiving AK treatment for the condition (Table 1). The patients were all referred by the kinesiologist who first requested permission to disclose personal contact information concerning participation in interviews about their experience of AK treatment, and their thoughts on health and trust. The interviews were open-ended, semi-structured without probing since prior knowledge of the outcome of the interviews was low. The interview guide was developed based on Kleinman’s Illness Explanatory Models [40] (Appendix 1). There were two individual meetings with each participant. The first meeting was the interview itself and lasted for 30–45 minutes, whereas the second meeting took place when the patient had received and validated a copy of the transcribed interview. The first interviews were conducted in the participant’s home; although in one case, a telephone interview was conducted. One follow-up interview was conducted in a café, one in the participant’s home and one over the telephone.

Table 1 Case study sample.

The interview questions concerned the patient’s personal experience of AK treatment and what the treatment has meant to them [41]. To counterbalance selection bias and possible preconceptions, fieldnotes were taken prior to, during and after each meeting with the participants [42]. The fieldnotes were utilized as an instrument to prepare the researcher for the process of interviewing and enabling the conscious process of separating the personal from the professional aspects of their role. The three participants shared their medical records of the MS diagnosis, the documentation of the progression of the disease and/or the progression of their MRI status. These medical records create a source of data separate from the interviews and were used with the recommendation from the local Ethics Committee. To create validity in an exploratory case study, Yin (2009) suggests several tactics, such as the use of multiple sources of evidence and allowing participants to review the data.

4.4 Data Analysis

Data were evaluated through phenomenological-hermeneutic text analysis. This method is frequently applied in qualitative humanistic studies in which the main body of data consists of narrative interviews that are recorded and transcribed producing a text for analysis [43]. Ricoeur [44] stated that “interpretation of the text constitutes a movement from understanding to explanation and from explanation to comprehension.” On the same note, Lindseth and Norberg (2004) explained their phenomenological-hermeneutic methodology as consisting of three working phases: naïve reading, structural analysis and comprehensive understanding. The goal of phenomenology is the collection and full description of vast bodies of data without reducing the richness of life or life experiences. Considering the exploratory aspect of the study, this method of analysis appeared suitable, encompassing an open-ended design for gathering data. The analysis consisted of an individual report of each case, followed by a cross-case analysis (Table 2) and the drawing of conclusions [39]. The validity of the analysis was confirmed by a co-researcher involved in the study, who held a PhD and whose research was based on qualitative methodology [37]. This retrospective study was approved by the regional research Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden (2014/373-31/1). All participants were guaranteed full confidentiality, and all gave informed consent to participate. The informants will have access to the analysis when finalized by receiving a personal copy of the study.

In this study, patients are at risk of re-living some of the hardships of their disease while providing their accounts, which might have psychological and emotional implications [37,45]. In such cases referral to professional counseling was prepared for.

Table 2 Cross-case synthesis.

5. Findings

5.1 Case Presentation and Naïve Understanding

Case 1. The woman interviewed in Case 1 was referred to the kinesiologist by family prior to having an incident of right body numbness and a loss of control over the right side of the body. During this incident, she sought hospital care and underwent a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan as well as a lumbar puncture (LP). A few months later, she was diagnosed with MS. The patient received interferon injections for four weeks but the treatment was stopped due to severe side-effects, including influenza-like symptoms. The patient sought AK treatment from the kinesiologist and after 1 year, she adopted the specific recommendation of the kinesiologist to exclude wheat, wheat starch and rye from her diet. Diet changes were essential and improved her sense of health and well-being. The hospital stated that they would perform follow-up MRIs 1 year after diagnosis; however, she was not contacted until 5 or 6 years later, which caused her to lose trust in the medical system. During this period, she had experienced improved health and gained trust in the kinesiologist.

Case 2. Case 2 was also a woman who sought treatment from the kinesiologist prior to being diagnosed with MS. The patient experienced episodes of dizziness, headaches, right body numbness and double vision, whereupon she sought medical care. The MS diagnosis was given quite quickly after an MRI and LP were performed, and she started medical treatment with interferon injections. Due to severe side-effects, including influenza-like symptoms, the injections were stopped after three months and she sought AK treatment from the kinesiologist. In this case too, the kinesiologist was recommended by a friend. The patient experienced having hope, which increased immediately following the primary AK treatment and enabled her to trust the kinesiologist. She made dietary changes instantly and stopped eating wheat and dairy products directly after being diagnosed with MS, thus causing her to realize that the diet changes were essential. The patient had been back to the hospital for MRIs a few times; however, at the time of the interview, she had not been contacted by the hospital for 5 years. The participant had not felt the need for medical consultations and experienced a loss of trust in the medical system.

Case 3. Case 3 was a woman who experienced loss of speech, right leg numbness, and double vision. After a month, most of the problems had subsided. The hospital continued to monitor her health status without providing a diagnosis for a further 4 years. The participant had two children before commencing any medical treatment. Nine years after the first MS episode, the patient reacted very strongly to analgesic injections during surgery to correct a hallux valgus. The patient described her own reaction as hysterical. Following this experience, the first relapse of MS occurred and the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) level escalated to 3. The patient was first treated with interferon injections, which she continued for 2 years in spite of severe side-effects, including influenza-like symptoms. At this time, she was referred to the kinesiologist through friends and sought treatment. At the time of interview, she had been receiving medical treatment and AK treatment in parallel for the previous 6 years, and the EDSS level had come down to 2, where it had remained for the previous 5 years. The patient had realized that diet changes were essential and had excluded wheat from her diet some years previously, although she made exceptions to the diet during vacations. She currently has remnants of right leg numbness and recurring balance problems, goes to a personal trainer (PT) and engages in physical training. She reported feeling confused facing the conundrum as to the cause of the symptoms and effects of her fitness regimen considering the restrictions of motherhood resulted in her being physically unfit. At the same time, she felt frightened by recurring falls and stumbling caused by right leg weakness and was uncertain as to what improvements were due to her medical and AK treatments. Due to her complex set of simultaneous lifestyle modifications and different treatments, she reported trusting the medical system, and trusting the kinesiologist as well as having hope.

5.2 Structural Analysis

During the first naïve reading and the subsequent structural analysis, different themes emerged from the interviews. The analysis of the transcribed interviews will be presented, highlighting the complexity of the individual cases as well as apparent similarities.

Having hope. In the quest for a healthy life, the patients in all three cases reported having hope in relation to having been diagnosed with MS. Having foresight is an important ingredient in coping with a serious ailment and participating in a process aimed at improving health. All three cases showed this aspect of experiencing hope when depression or darker feelings could have been expected considering the chronic aspect of MS.

“When I received this new diagnosis of MS, the kinesiologist could immediately remove the worst symptoms and then we could all go on vacation, the whole family actually.”

Trusting the kinesiologist. All three patients recollected how they felt able to trust the kinesiologist immediately on commencing treatment. This sense of trust had remained throughout years of receiving AK treatment. The ability to trust was referred to by all as a vital element of their treatment, motivating them to comply with the kinesiologist’s advice to avoid wheat and/or rye and/or dairy products, taking the prescribed herbal medication and vitamin supplements, and continuing treatment.

“When you go for AK treatment, you get a lot of confidence in the kinesiologist because if you have a problem, you do not have to say it, he finds it and it's quite fascinating but very hard to tell others who have not met him.”

And:

“Yes, I do trust him, because I've had results so many times, indicating he knows what he's doing. You will get help when you go there.”

Diet changes essential. Excluding wheat from a diet while living in a Western country requires a distinct effort, since one has to read all labels on all food and be interrogative at all times in restaurants and public places that serve food and beverages. All three cases made major dietary changes and found this essential to the improvement of their health.

“So I do think that I am allergic to wheat flour more than that I have MS basically, or maybe that I have the tendency towards MS in the body.”

The patient in Case 3 stated that she made exceptions to the dietary restriction during vacations, and said that she refused to feel guilty about this, meaning that she had to live her life.

Losing trust in the healthcare system. The patients in both Case 1 and Case 2 lost their trust in the healthcare system during the process of commencing AK treatment. Both women had not been contacted by the healthcare system for a period of 5 years; however, the feeling that they had been forgotten was not directly linked to their loss of trust in the healthcare system. Rather the loss of trust was due to various reasons and conditions appearing as a result of, and including, the overall aspect of experiencing a sense of health.

“Yes, I have confidence in the kinesiologist. But then, I do not have the same confidence in the healthcare service, no.”

Both patients stated feeling that changes of diet and the effects it has on ailments and chronic conditions were not a consideration of the healthcare system. Based on the changes in lifestyle made by all three patients, they further claimed feeling that the medical system would only consider aspects of lifestyle such as physical training.

“I have no confidence at all in regular medical care, I do not go to the doctor unless I've broken my leg or something like that. So no, I do not trust what they are saying.”

Feeling confused. The patient in Case 3 reported trusting both the kinesiologist and the healthcare system and received treatment from both simultaneously. She recollected that the kinesiologist had told her that she could refrain from medical treatment; however, she stated that even though she trusted the kinesiologist, her trust was not blind, so she did not want to stop medical treatment. She was feeling confused as to what was helping to improve her health, since she was working with a PT, had made dietary changes, received medical and AK treatment and was advancing in her professional position.

“The question is, the body is not so logical, or well, maybe it is, but it's hard for a normal person to know what's what.”

Getting better. All participants experiencing positive results rapidly following AK treatment, which all described as having been a great motivator for continuing with the treatment. They all recollected experiencing improved health immediately following a treatment, some even at the point of leaving the consultation room.

“The stomach is better. I was really in pain after the hallux valgus surgery, and then I got other problems in my foot. I do not know if this often happens, but I got Morton syndrome, with pain in your nerves. That completely disappeared when I got AK treatment and I need much less sleep.”

5.3 Comprehensive Understanding

The naïve reading was validated by the structural analysis. This process entailed referring to both the naïve reading and the structural analysis based on condensed descriptions [43]. A comprehensive synthesis of the structural analysis is shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Thematic synthesis.

Making changes for life. In all three cases, the patients made substantial dietary changes recommended by the kinesiologist and all were convinced of the benefits that accompanied these sacrifices and changes. They experienced a sense of increased control over the risk of a MS relapse. The two women who had been following the kinesiologist’s recommendations were well. The health of the patient who was following the kinesiologist’s recommendations and simultaneously receiving conventional medical treatment had stabilized. She also experienced improved health immediately after each AK treatment although the improvements may not have happened exactly as she had hoped; for example, although she first sought treatment for right leg weakness, the most significant positive change she experienced was improvements in her stomach condition. Furthermore, the patient was continually concerned about maintaining this condition that had improved her life.

Getting past the diagnosis of MS. All participants shared their medical records showing a diagnosis of MS by an MD. The patients in Cases 1 and 2 trusted the CAM practitioner and were feeling healthy. Neither of them identified themselves by their condition and had medical records showing that their MRIs did not indicate an increasing severity of MS. However, their medical records did not state that they were MS-free, which is to be expected since the medical world considers MS to be incurable. Following the primary medical treatment with interferon, all the patients had almost identical experiences of an influenza-like syndrome lasting for a day or two after the injection. All the patients explained how they were able to live beyond the MS diagnosis, with the patients in Cases 1 and 2 not identifying with the MS diagnosis at all. The patient in Case 2 said that she usually told people that she had recovered from MS, despite being acutely aware that this is highly improbable. The patient in Case 3 said she had MS but that there were much worse things in the world and she did not feel impaired by the condition, nor was she afflicted by relapses.

Experiencing health through AK treatment. The AK treatment had given the participants a sense of hope, trust and increased health. All the participants had been able to create a bridge traversing fear and despair, not to mention hopelessness, and had found the courage and bravery necessary to try new treatments and make way for experiencing health. That illustrates a concept of health as a holistically defined sense based on the individual and specific experiences of each person receiving AK treatment involving herbal medication, vitamin supplements, dietary changes, physical exercise and in one case, combining all of these elements with conventional medical treatments.

6. Discussion

The apparent serendipity and outstanding coincidence surrounding the circumstances by which the patients in Case 1 and Case 2 found the kinesiologist prior to having been diagnosed with MS was an extraordinary ingredient in their individual treatment and its success. The ramifications of this remain unclear, since it was not the subject of study, but rather an aspect revealed during the study. All three cases have reported unconditionally seeking AK treatment, implying that they had been prepared to make life changes and “take the leap of faith” required to bridge the gap. Such action requires bravery considering the biomedical paradigm in conjunction with the limitations of evidence for the effectiveness of CAM treatments. Rather, it relies heavily on the individual´s courage and quest for a healthier life, displaying self-awareness and self-care [46].

This cross-case synthesis shows that AK treatments warrant further investigation (Table 2). A comprehensive understanding of AK is necessary considering the absence of a cure for the chronic condition of MS, in addition to the absence of conclusive evidence for the etiology and effects of medication [6]. This study indicates the potential scientific relevance of AK treatment based on the parallel stabilization of the MRI scans during the treatment periods in all three cases combined with the real-life experience of increased health; therefore, these findings urgently need further investigation. Hope and trust were shown to be important factors in the complex relationship between doctor/practitioner and patient. The content of AK treatments cannot be evaluated in this present study; it was not subject of this research. The present study aimed to describe the patients’ experiences of AK treatment for MS. Two of the participants appeared so well that they did not feel impaired, struck by illness, or in need of medical treatment, despite apparently being lost to the medical system. In Case 3, the EDSS level decreased from level 3 to level 2 and had remained stable for the 5 years prior to the study, also indicating stability and recovery. This indicates that AK treatments have improved the patient’s experience of health.

All three women were happy and were not afflicted by depression [47] caused by the loss of health, their mental robustness having improved with their physical health. They were content with the kinesiologist and their AK treatments. The patients in Cases 1 and 2 clearly stated that trusting the practitioner was of the utmost importance and neither patient trusted the medical system; in contrast, the patient in Case 3 trusted both the kinesiologist and the medical system. The main conclusion from this is that trust contributed the experience of AK treatment, resulting in a “no fear” existence for all three patients. In all three cases, the patients had, to some degree, received treatment from the medical system, changed their diets, experienced improved health, trusted the kinesiologist, and practiced physical exercise; all of which were indicative of an underlying broader definition of health. All three patients had a holistic health experience that allowed them to transcend their diagnosis of MS.

6.1 Methodological Considerations

The validation of the interviews was uncomplicated; while reading the transcribed interviews, all participants made only minor corrections, with no factual errors, just minor misunderstandings. This study is a best-case scenario with a certain amount of bias and selection bias considering that patients were referred by the treating kinesiologist [38,45]. Malterud [38] claims that the retrospective casuistry in medical research is usually based on a so-called “Eureka moment” that one later wants to relate to others. External validity is not considered the stronghold or the purpose of qualitative studies [45], although Malterud reminds us that the English physician Edward Jenner discovered the principle of smallpox vaccination in the year 1796 based on a single case study. Kvale further opines that ”to validate is to investigate”, suggesting that validation should be conducted throughout the research. For the same reasons, Yin (2009) also suggests using replication logic in the design of multi-case studies. To generate validity in this exploratory case study, multiple sources of evidence were utilized [39,48], and Malterud [49] similarly states that “the validity of clinical evidence can be strengthened when qualitative and quantitative methods complement each other”.

Future studies are needed to examine patient experiences of AK treatments and to assess whether AK treatments are experienced as transformative as they were in the present study. The participants should be enrolled on the basis of open exit selection. Future studies on AK treatment, both as a diagnostic and a therapeutic tool, are of importance for furthering our scientific understanding of this method. Future rigorous research with the capacity to produce reliable evidence regarding CAM theories and practices are of importance for the safety of patients.

7. Conclusion

In this case study of three women who sought AK treatment for MS, all three patients reported being able to make changes for life, getting past their diagnosis of MS and being able to experience increased health through AK treatment. In relation to the phenomenological narratives in illness studies, our findings suggest that the interviews in this study are phenomenological-hermeneutic narratives of health, as well as describing experiences of becoming at one with the body. The interviews also assess the value of AK treatments as a holistic approach assisting patients in sculpting the living body [50] into the home-likeness of being-in-the-world [33], experiencing becoming whole, and experiencing health. In each of the cases reported here, the MRI results were stabilized during the AK treatment period and all three patients felt able to transcend their diagnosis of MS.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all three patients for sharing their lived experiences of seeking AK treatment for the affliction of MS, to the kinesiologist for sharing patient referral contact information and for having sought primary consent from the patients to participate in the research.

Author Contributions

The authors have contributed in all stages, from formulation the project, development, reading, analysing, discussing, and writing. Katarina has been the initiative-taker, and coordinator and was responsible for manuscript editing. Data and material are available upon request with respect to the integrity of the participants.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

List of Abbreviations

AK Applied Kinesiology

CAM Complementary and Alternative Medicine

EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale

LP Lumbar puncture

MD Medical Doctor

MMT Manual Muscle Testing

MS Multiple Sclerosis

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

PT Personal trainer

Appendix 1: Interview Guide

CAM & MS 2017-10-10

1. Can you tell me what it was like to get MS and what it has meant for you?

2. The treatment you received with kinesiology, what has it meant for you? How did you experience kinesiological treatment?

3. How do you experience your health today?

4. Can you give me personal information about your age, family situation, education and occupation?

5. How do you look at the future?

6. Do you have medical data showing that you have been diagnosed with MS and how your test questions (MR and LP) have looked like, can I see them?

Follow-up Interview:

1. Have you read the transcribed interview and do you think it is correct, as it has been transcribed?

2. What is health, how does it occur and how is it maintained?

3. Is trust important to you in your relationship to health?

References

- Farinotti M, Vacchi L, Simi S, Di Pietrantonj C, Brait L, Filippini G. Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 12: CD004192. [CrossRef]

- Olsen SA. A review of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by people with multiple sclerosis. Occup Ther Int. 2009; 16: 57-70. [CrossRef]

- Apel A, Greim B, Konig N, Zettl UK. Frequency of current utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006; 253: 1331-1336. [CrossRef]

- Jaremo P, Arman M, Gerdle B, Larsson B, Gottberg K. Illness beliefs among patients with chronic widespread pain - associations with self-reported health status, anxiety and depressive symptoms and impact of pain. BMC Psychol. 2017; 5: 24. [CrossRef]

- Nayak S, Matheis RJ, Schoenberger NE, Shiflett SC. Use of unconventional therapies by individuals with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2003; 17: 181-191. [CrossRef]

- Gottberg K, Gardulf A, Fredrikson S. Interferon-beta treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis: the patients' perceptions of the side-effects. Mult Scler. 2000; 6: 349-354. [CrossRef]

- Pucci E, Cartechini E, Taus C, Giuliani G. Why physicians need to look more closely at the use of complementary and alternative medicine by multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol. 2004; 11: 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Sinha AA, Lopez MT, McDevitt HO. Autoimmune diseases: the failure of self tolerance. Science. 1990; 248: 1380-1388. [CrossRef]

- Sospedra M, Martin R. Antigen-specific therapies in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Immunol. 2005; 24: 393-413. [CrossRef]

- Isaksson AK, Ahlstrom G, Gunnarsson LG. Quality of life and impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005; 76: 64-69. [CrossRef]

- Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS, Czarnecki D, Dmochowski J, Henschel K, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Mult Scler. 2000; 6: 181-185. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Hansen HJ, Bach FW. Sensory function and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain. 2005; 114: 473-481. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Overvad K, Hansen HJ, Koch-Henriksen N, Bach FW. Pain in patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2003; 60: 1089-1094. [CrossRef]

- Filippini G, Del Giovane C, Clerico M, Beiki O, Mattoscio M, Piazza F, et al. Treatment with disease-modifying drugs for people with a first clinical attack suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 4: Cd012200. [CrossRef]

- Clerico M, Faggiano F, Palace J, Rice G, Tintore M, Durelli L. Recombinant interferon beta or glatiramer acetate for delaying conversion of the first demyelinating event to multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; CD005278. [CrossRef]

- Munari L, Lovati R, Boiko A. Therapy with glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; CD004678.

- Bowling AC. Complementary and alternative medicine and multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2011; 29: 465-480. [CrossRef]

- Kochs L, Wegener S, Suhnel A, Voigt K, Zettl UK. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Complement Ther Med. 2014; 22: 166-172. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz S, Knorr C, Geiger H, Flachenecker P. Complementary and alternative medicine for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008; 14: 1113-1119. [CrossRef]

- Spain R, Powers K, Murchison C, Heriza E, Winges K, Yadav V, et al. Lipoic acid in secondary progressive MS: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017; 4: e374. [CrossRef]

- Yadav V, Shinto L, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010; 6: 381-395. [CrossRef]

- Yadav V, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine: is there a role in multiple sclerosis? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006; 6: 259-267. [CrossRef]

- Fowler S, Newton L. Complementary and alternative therapies: the nurse's role. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006; 38: 261-264. [CrossRef]

- Shinto L, Calabrese C, Morris C, Sinsheimer S, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: survey of licensed naturopaths. J Altern Complement Med. 2004; 10: 891-897. [CrossRef]

- Shinto L, Yadav V, Morris C, Lapidus JA, Senders A, Bourdette D. Demographic and health-related factors associated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006; 12: 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Rosner AL, Cuthbert SC. Applied kinesiology: distinctions in its definition and interpretation. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012; 16: 464-487. [CrossRef]

- Waxenegger I, Endler PC, Wulkersdorfer B, Spranger H. Individual prognosis regarding effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention using pre-therapeutic “kinesiology muscle test”. Scientific World Journal. 2007; 7: 1703-1707. [CrossRef]

- Molsberger F, Raak C, Witthinrich C. Improvements in sleep and handwriting after complementary medical intervention using acupuncture, applied kinesiology, and respiratory exercises in a nine-year-old ADHD patient on methylphenidate. Explore (NY). 2014; 10: 398-403. [CrossRef]

- Molsberger F, Raak C, Teuber M. Yamamoto new scalp acupuncture, applied kinesiology, and breathing exercises for facial paralysis in a young boy caused by lyme disease-a case report. Explore (NY). 2016; 12: 250-255. [CrossRef]

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture : an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. 1980; xvi: 427 p.

- Toombs SK. The meaning of illness : a phenomenological account of the different perspectives of physician and patient. Dordrecht: Kluwer. 1992; 161 s. p. [CrossRef]

- Carel H. Phenomenology as a resource for patients. J Med Philos. 2012; 37: 96-113. [CrossRef]

- Svenaeus F. Illness as unhomelike being-in-the-world: Heidegger and the phenomenology of medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 2011; 14: 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Zollman C, Vickers A. What is complementary medicine? BMJ. 1999; 319: 693-696. [CrossRef]

- Galvin K, Bishop M. Case studies for complementary therapists: a collaborative approach. 1st ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Andermo S, Sundberg T, Forsberg C, Falkenberg T. Capitalizing on synergies-a discourse analysis of the process of collaboration among providers of integrative health care. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0122125. [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg K. Kvalitativa metoder för vårdvetare. 2., [rev.] uppl. ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1997; 153 s. p.

- Malterud K, Midenstrand M. Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning : en introduktion. 2. uppl. ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2009; 244 s. p.

- Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 4th ed. London: SAGE; 2009.

- Kleinman A. The illness narratives : suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books; 1998; xviii: 284 p. p.

- Dahlberg K, Todres L, Galvin K. Lifeworld-led healthcare is more than patient-led care: an existential view of well-being. Med Health Care Philos. 2009; 12: 265-271. [CrossRef]

- Sanjek R. Fieldnotes : the makings of anthropology : Symposium : 84th Annual meeting : Revised papers. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1990.

- Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004; 18: 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Ricoeur P. Interpretation theory : discourse and the surplus of meaning. 2. pr. ed. Fort Worth, Tex.: Texas Christian U.P; 1976; 107 s. p.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. InterViews : learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3., [updated] ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2015; xviii: 405 s. p.

- Arman M, Hok J. Self-care follows from compassionate care - chronic pain patients' experience of integrative rehabilitation. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016; 30: 374-381. [CrossRef]

- Gottberg K, Chruzander C, Backenroth G, Johansson S, Ahlstrom G, Ytterberg C. Individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy in multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Clin Psychol. 2016; 72: 651-662. [CrossRef]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods : integrating theory and practice. Fourth ed. SAGE Publications; 2015.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001; 358: 483-488. [CrossRef]

- Nightingale F. [Notes on Nursing. What it is and what it is not ... A facsimile of the first edition published in 1860 by D. Appleton and Co., etc.]. New edition, revised and enlarged. ed: London; 1860.