The Lived Experience of Individuals with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury: An Adapted Group Yoga Intervention

Megan A. Roney, MS, OTR/L 1, 2, † ![]() , Pat L. Sample, PhD, MDiv 1, †

, Pat L. Sample, PhD, MDiv 1, † ![]() , Lorann Stallones, PhD, MPH 3, †

, Lorann Stallones, PhD, MPH 3, † ![]() , Marieke Van Puymbroeck, PhD, CTRS, FDRT, RYT-200 4, †

, Marieke Van Puymbroeck, PhD, CTRS, FDRT, RYT-200 4, † ![]() , Arlene A. Schmid, PhD, OTR, FAOTA, RYT-200 1, †, *

, Arlene A. Schmid, PhD, OTR, FAOTA, RYT-200 1, †, * ![]()

- Colorado State University, Department of Occupational Therapy, Fort Collins, CO, US

- Amaryllis Therapy Network, Denver, CO, US

- Colorado State University, Department of Psychology, Fort Collins, CO, US

- Clemson University, Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management, Clemson, SC, US

† These authors contributed equally to this work.

* Correspondence: : Arlene A. Schmid, PhD, OTR ![]()

Academic Editor: Gerhard Litscher

Received: November 4, 2018 | Accepted: December 13, 2018 | Published: December 17, 2018

OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018, Volume 3, Issue 4 doi: 10.21926/obm.icm.1804033

Recommended citation: Roney MA, Sample PL, Stallones L, Van Puymbroeck M, Schmid AA. The Lived Experience of Individuals with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury: An Adapted Group Yoga Intervention. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 2018; 3(4): 033; doi:10.21926/obm.icm.1804033.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

Background: An adapted yoga intervention was delivered to seven individuals with chronic traumatic brain injury. The purpose of this study was to explore and describe the participants’ experience of engaging in the 8-week intervention.

Methods: Using a phenomenological design, data were collected, analyzed, and coded to generate themes regarding experiences that occurred, how experiences occurred, and why experiences occurred.

Results: Participants described experiencing the yoga intervention as a process: from initially expecting only physical benefits; to feeling physically and emotionally safe and comfortable in the yoga environment; to experiencing physical, emotional, and cognitive changes. Participants described their experiences as positively impacting their daily lives, health maintenance, and social participation. Participants attributed various reasons for their experiences, including commonalities among participants, the yoga teacher’s dual knowledge of yoga and occupational therapy, and the adaptability of yoga to their personal needs.

Conclusions: The participants’ expressions of beneficial outcomes indicate the need to further research adapted yoga interventions for individuals with chronic traumatic brain injury. Additionally, the impact of yoga practice on participants’ daily life has great implications for therapeutic rehabilitation and merits further exploration.

Graphical abstract

Keywords

Traumatic brain injury; yoga; occupational therapy; rehabilitation

1. Introduction

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is caused when an individual experiences a bump, blow, or jolt to the head causing a disruption of brain functioning [1]. The occurrence of these injuries is a global public health problem that can result in a wide range of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and physical changes for the affected individual [1,2]. Many individuals with TBI report experiencing cognitive impairments in addition to poor physical health in the first year post-injury, which affect social integration and ability to work [3,4]. The effects of a chronic TBI negatively influence engagement in daily life occupations, or purposeful activities valued by the individual, including social interactions and participation in community life [3,5,6,7,8,9]. Due to the long-term negative effects of TBI, it is imperative to explore rehabilitation options for individuals beyond the acute TBI recovery phase, in order to promote success in daily life post-injury [3,6].

One rehabilitation possibility for people with chronic TBI is adapted yoga, including physical postures (asanas), breath work (pranayama), and meditation (dhyana) [10,11]. Support for yoga as an intervention in clinical settings is growing as researchers indicate positive outcomes for populations with various medical conditions including cancer, diabetes, schizophrenia, chronic low back pain, post-stroke disability, arthritis, prenatal depression, multiple sclerosis, menopause, posttraumatic stress disorder, cardiovascular disease, restless leg syndrome, insomnia, heroin detoxification, and migraine. [10,12]. Researchers have found that individuals with chronic conditions who practice yoga may experience improved cognitive functioning, self-awareness, balance, coordination, adjustment to disability, and reduced stress [10,11,13,14]. Because of these benefits, yoga has been suggested as a modality to address many deficits faced by individuals with chronic TBI [15].

The study of yoga as an intervention for individuals with TBI is still in preliminary stages. However, pilot studies and studies that incorporated yoga as one element of rehabilitation have demonstrated initial feasibility and efficacy of yoga for individuals with TBI [8,16,17,18,19,20]. In a case study three participants with chronic TBI participated in 8 weeks of one-on-one yoga instruction resulting in improvements in balance, lower extremity strength, and endurance [21]. During interviews, participants described a return of valued occupations such as playing the piano and golfing. One participant also discussed an increase in social participation, which he attributed to bolstered stamina as a result of practicing yoga [21]. In a pilot study of the effects of breath-focused yoga for adults with severe TBI, participants self-reported improvements in physical functioning, emotional well-being, and overall health over time, further substantiating the value of yoga for individuals with TBI [19]. While these studies provide preliminary research in support of yoga as an intervention delivered in a 1:1 session, there is still a need for continued research of the effect of yoga for individuals with TBI in a group setting [16,19,20]. Furthermore, there is little understanding of the in-depth experiences of individuals with TBI who participate in yoga.

Phenomenological research has shown that individuals with TBI express a relationship between the personal meaning they associate with an activity and their experience of feeling engaged while performing said activity [5]. The effect of personal meaning on engagement has significant implications for research exploring effective interventions for individuals with TBI. An association of personal meaning with intervention activities may influence engagement, and therefore continuance and efficacy. Acknowledging the individual’s experience through personalized, empathetic care is a perennial objective of professionals in delivering high-quality healthcare service [22]. Attaining this level of care means focusing on an individual’s self-perceived experience when designing and implementing interventions in order to enhance outcomes [23]. One way to progress toward this goal is through the expansion of phenomenological inquiry into efficacy and feasibility studies in order to understand the individual’s lived experience of the intervention [5,7,24]. The current study used a phenomenological approach to obtain rich narrative data to inform the understanding of how individuals with TBI experience an adapted yoga intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Design

Two researchers of this study used a qualitative phenomenological approach to describe common meanings [25] among participants with chronic TBI, who together engaged in an eight-week yoga intervention. During focus groups and interviews throughout the intervention, the researcher asked the participants to reflect on what they experienced while practicing yoga, how they experienced practicing yoga, and why they felt they experienced the intervention in the way they did. Institutional Review Board approval was received for the full study. All participants provided written consent prior to participating in the study.

2.2 Researchers’ Positions

The research team for this study included two professors of occupational therapy (OT), one professor of epidemiology, one professor of recreational therapy, and one graduate student completing her master’s degree in OT. The first author experienced a TBI due to a car collision in 2004, practiced yoga throughout her rehabilitation, and continues to practice yoga. She analysed the data alongside the second author, who acted as a triangulating data analyst. The triangulating analyst’s primary research focuses on identification, service needs, service access, and life outcomes of people with TBI. We acknowledge that our personal and professional bias concerning brain injury possibly influenced our perspectives, but we attempted to limit individual bias through multiple data validation strategies [25].

2.3 Recruitment and Participants

We recruited a convenience sample of seven participants from a midsize university city in Colorado. Recruitment included posting flyers in a rehabilitation hospital and the office of a university program for student veterans. Additionally, two authors presented the study to potential participants in a TBI support group. The inclusion criteria were: a period of six months or more since the TBI; self-reported balance impairment defined as participant report of worry or concern about balance in daily life activities; and no consistent engagement in yoga for at least one year prior to participation in the study. Participants were excluded if they self-reported exercise restrictions, consistently practiced yoga during the previous year, or were unable to attend yoga sessions due to transportation issues. Prior to commencement of the study, participants gave written consent to participate in this Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study. Participants received a 25 gift card to assist with the cost of transportation to yoga sessions.

An initial hour-long interview was conducted with each participant prior to the beginning of the study. We sought to gather background information, to develop a relationship of mutual trust between participant and researcher, and to increase the participants’ comfort in sharing information, thereby committing to follow through with the intervention. The primary researcher conducted all initial interviews in which she asked participants to describe a typical day; illuminate on perceived physical, mental, and emotional strengths and weaknesses since TBI; and to describe personal values. We did not include the information contained in these initial interviews in our data analyses, since the purpose of this study was to describe the yoga class experience, not the background information reported in the pre-yoga interviews. All but two participants had some prior yoga experience, but none had practiced consistently. The average age of participants was 56.43 with a standard deviation of 7.35 years, and four (57%) were female (see Table 1 for additional demographics). Pseudonyms were used to protect confidentiality.

Table 1 Participant demographics.

2.4 Intervention

The intervention was held in a university research laboratory near the Rocky Mountain foothills. The intervention consisted of one-hour, bi-weekly group yoga sessions for eight weeks (16 total sessions). A registered yoga teacher who is also a registered and licensed occupational therapist (OTR/L) taught the yoga sessions. The yoga protocol was adapted from a prior study [16] to specifically target the needs of individuals with TBI in a group setting. The yoga protocol consisted of physical postures, breath work, affirmations, and meditation. The yoga programming aimed to improve balance, strength, flexibility, and dynamic weight shifting.

As the class progressed, physical postures advanced in difficulty and moved from sitting, to standing, to laying supine. Modifications were provided throughout the intervention to accommodate varying abilities and preferences. Physical props (e.g. bolsters, straps, blocks, blankets) were used to facilitate support in certain postures. Two research assistants were available during each session to assist in posture adaptations.

Beginning in week three, participants were encouraged to synchronize their breath with a statement of affirmation, a practice adapted from the Twelve Step philosophy of internally repeating a statement in coordination with breath to inspire positive thought [26,27]. Affirmations were simple statements that varied from session to session with foci on self-integrity and self-awareness (see Table 2). The decision to refrain from introducing affirmations until week three reflected our attempt to create a conducive learning environment by systematically building upon yoga concepts as the intervention progressed.

Table 2 Affirmations used during session one and two of each week.1

2.5 Data Collection

Qualitative data, exclusively, were collected for this study by way of an audio-recorded focus group held mid-way through the intervention; an audio-recorded focus group at the end of the intervention; and individual interviews following the intervention. After each interview, the primary researcher recorded field notes regarding important nonverbal, atmospheric, and sensory detail [25]. Additionally, she recorded descriptive observations during yoga classes and her own reflections throughout the study.

We held both focus groups at the yoga research laboratory after yoga sessions, with the first author facilitating the discussion, and another researcher recording the answers on a white-board, for participants to reference. Questions were structured based on a focus group guide [28,29] and were open-ended to elicit participants’ personal experiences of the yoga intervention. See Table 3 for sample questions. Focus groups lasted 45 minutes to an hour.

The first author conducted individual interviews upon the completion of the intervention to elicit each participant’s personal experience of engagement in yoga. Interviews were semi-structured and loosely followed a guide of open-ended questions. The flexibility of the interviews allowed conversation to take a natural form and created an environment that encouraged each participant’s free expression of his/her experience [25]. Probing questions were used following responses that merited clarification or amplification. Interviews took place in the participants’ homes to strengthen the interviewee’s comfort level and allow for observation of the participant in his/her natural environment. Interviews lasted from 30 to 90 minutes.

Table 3 Sample focus group/interview questions.

2.6 Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the primary author. The interviews were then played aloud again while the primary author read through the transcription to ensure the transcription aligned with the interview exactly. The primary author and the triangulating analyst thoroughly read each transcript, recorded initial thoughts and comments, and identified preliminary categories of data with the use of the precise words of participants [25]. Both researchers met on several occasions to triangulate multiple sources of data including direct quotations, field notes, and parenthetical information referring to environmental context in transcripts. In these meetings researchers identified preliminary “clusters of meaning” or categories of data with the use of the precise words of participants [25]. They then adhered to the following procedure suggested by Creswell [25] for examining phenomenological data. See Table 4 for an excerpt of the coding scheme.

Table 4 Coding scheme example.

To increase the rigor of the study, we employed multiple validation strategies including: clarification of researcher bias; prolonged engagement and persistent observation; triangulation of data and analysts; and thick, rich description [25]. Use of all strategies was documented through a detailed audit trail of the analysis. Clarification of researcher bias involved positioning, or the clarification of the individual researcher’s relationship to the study data and biases that may exist as a result. We included researcher reflexivity through the discipline of memoing throughout the coding process. Triangulation occurred through gathering data from multiple sources including: individual interviews, focus groups, field notes, and observations. The triangulating analyst was used to: keep the primary author and research honest; ask challenging questions about methods, meanings, and interpretations; and provide the opportunity for catharsis by sympathetically listening to the researcher’s feelings [25]. Finally, thick and rich description, including detailed information regarding the study participants and setting, was used in field notes, observations, and the data analysis audit [25]. These validation strategies increased the rigor of the study and helped to ensure soundness of the study findings.

3. Results

In the following section quotes of individual participants are used to substantiate reoccurring themes found throughout the data. Table 5 provides a summary of results organized by each participant. All seven participants completed the entire 8-week intervention.

Table 5 Results.

3.1 “Trust the Process”: Essence of the Experience.

The participants’ descriptions of their experiences changed and grew as they progressed through each sequential yoga session. Fiona described her experience of relating to her physical body through yoga as a process:

I just got this general message telling me that it’s normal and that it’s ok to, you know, pay attention to your body, and that was a hard one for me, but just having the awareness, that, you know, gives you what to look for…it takes a while…and you can trust the process. That’s kind of the messages that I heard.

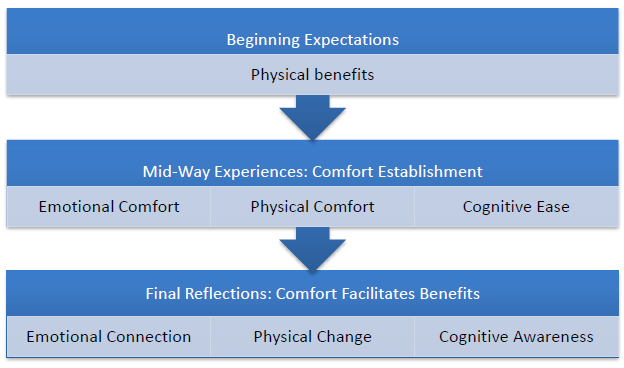

Similar progressions appeared repeatedly in the data, and therefore results are presented chronologically. Reflections describing beginning expectations before the intervention, mid-way through the intervention at four-weeks, and at the conclusion of the intervention are presented to reflect the experience as the participants progressed through the 16 yoga sessions (see Figure 1). The themes describe broadly what the participants experienced during the group yoga intervention and subthemes describe more specifically how yoga was experienced. An additional theme characterizes the ways in which participants’ experiences affected their daily life activities beyond the yoga intervention.

Figure 1 Chronological model of the adapted yoga intervention essence of the experience.

3.2 Beginning Expectations: Physical Benefits

In individual interviews at the end of the study, participants were asked to reflect upon their original motivation for participation and what they expected to experience. Reasons for deciding to participate in the intervention varied among participants, but all expectations related to hopes for improved physicality. For example, Ann hoped the intervention would offer a means of re-engaging in a health-promoting activity.

I had done yoga in the past, and I hadn’t done it for many years…I knew the study was being done to help coordination, balance, and I was having trouble with that, and I thought that I would give it a try, and I thought it would be a good way to get back into doing yoga again if it was helpful.

While other participants had less or no experience with yoga, they expressed hearing about the benefits of yoga and hoped it would have positive physical effects including increasing balance and decreasing pain.

Cari: I didn’t expect it [yoga] to make any big difference in my life, but I knew that I needed to, you know, just because so many people do it, I figured there’s probably something there that I’ve been missing.

Fiona: What I did expect was, you know, to learn some specific poses, techniques that would help with some of my physical pain.

Dan described exploring alternative therapeutic options and yoga being offered as a suggestion by his neurologist. He explained that he expected yoga to be more physically taxing than what he experienced, “I thought it was stretching, which it kinda is, but I didn’t know it would be relaxing cause typically when you’re doing exercises and stuff it’s like work.”

Erin anticipated having difficulty with physical aspects of yoga:

I know yoga is good for you, but I took a yoga class over at [athletic club] and they were doing hump dogs and all those, and that’s so hard. You know? I thought it would be that.

3.3 Mid-Way Experiences: Physical, Emotional, and Cognitive Comfort

During the mid-way focus group, participants were asked to describe their experiences up to the halfway point and their hopes for the remainder of the intervention. Broadly, all participants described feelings of comfort in the form of: physical comfort and relaxation; emotional comfort and safety; and cognitive ease. Various intentional environmental strategies built into the intervention facilitated the participants’ experience of comfort. Strategies included: the insurance of commonality among participants through use of inclusion criterion of similar diagnosis, maintenance of a relaxing sensory environment within the intervention space, modification of physical postures, and helping the participants to recognize that yoga poses should not be painful.

Emotional comfort and safety through participant commonality. Emotional comfort was a common experience expressed by most participants and was described as feeling safe and more able and willing to open up to others in the group. Experiences of emotional comfort were attributed to connections between participants including commonalities of TBI and involvement in the local brain injury support group. As some participants described, these commonalities fostered a less intimidating environment than they expected to experience while practicing yoga.

Fiona: I think for me the safety definitely comes from the connection of head injury, and the reason why I have a head injury is more psychological, but it doesn’t take away from the fact that we all have that connection, and to me that makes such a difference, you know? Ability to open up and learn and know that everybody’s in that space, and I don’t know, that’s what made it safe for me.

Cari: Maybe because it’s this size, maybe it’s because also I know a lot of the people here from the support group, or whatever, but I definitely feel safer here, more relaxed.

Physical comfort and relaxation through experiencing adapted yoga. Relaxation and physical comfort were also common experiences among participants. For Bill, relaxation was facilitated through re-conceptualizing how yoga should make his body feel.

Well, there was pain with a lot of the courses [I've taken before], and a lot of the poses, and I thought it was supposed to be that way, and I enjoyed this a lot more…there’s not a lot of pain here. There’s none in fact…I’m kinda glad this is different than that kind of yoga because this is very relaxing, compared to that especially. To call it yoga, I have a hard time with that, but it’s yoga in a different form, and it’s a lot better.

Dan recalled the first day of class, and wished the yoga teacher had been clearer about the idea that yoga should not hurt:

Back like the first day I either didn’t get the message that – the no pain thing, or I’m not sure if she didn’t say it…but I think for the first time, you should say that up front.

For other participants, relaxation was facilitated through focusing on breath and using breath in combination with movement through physical postures, a key component of yoga taught throughout the intervention:

Ann: It’s reminding me to stay aware of my breath cause I think I was holding my breath a lot…I think just everyday, I was holding my breath a lot just from stress, anxiety, you know? And it’s reminding me to breathe, to remember to breathe.

Gi described using the cat and cow postures in combination with his breath to reduce stress in his daily life.

I really feel that the cow and the cat just helps me…I feel like that’s really helped me when I get stressed out. I just take some time and I’ll move forward on the couch or wherever and I’ll just breathe and breathe, breathe.

Fiona expressed difficulty with being aware of both her body and breath, but hoped to improve in this area as the intervention continued.

Sometimes I’m really uncomfortable being aware of my body, and just focusing on a certain area, and that’s something that I hope to improve. Focusing on my breath is another thing…so there are some things that are really uncomfortable, but I hope that in time it will improve.

Several participants described the yoga teacher’s role in facilitating physical comfort through modifications or adaptations of the poses. Cari described how the yoga teacher’s adaptations to a series of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal eye movements helped relieve her physical discomfort.

She [yoga teacher] has been so good at helping with modifications like the eye movements. I can’t do that. I get too nauseous and all sorts of stuff, and, you know, other areas that I talk to her about, which I don’t remember anymore because she told me what to do to modify. Now I’m modifying it. I don’t remember what I’m modifying, but it has helped.

Ann and Erin also spoke about learning to adapt the eye movements to fit the needs of their bodies. Ann switched to using arm movements to cross midline because she felt like using her eyes would trigger a seizure. For Erin, the eye movements were used at times to replace crossing midline with her arm due to pain she experienced as a result of paresis in her shoulder.

Additionally, participants described appreciation for instruction in using provided props to aid in physical comfort while in various postures. Participants also cited the yoga teacher’s voice and choice of music as increasing experiences of relaxation. These aspects of tactile and auditory input furthered the establishment of comforting experiences.

Cognitive ease through instruction adaptations. Participants experienced cognitive ease through the yoga teacher’s adaptation of the instructions. They described her abbreviation and repetition of both instructions and affirmations as helpful in aiding memory.

Ann: I like that the instructor is aware that we have brain injuries and so she shortens – abbreviates the affirmation at the beginning of class, keeps the instructions short…short and easy to remember. Stays in our head.

Dan also described the adapted instructions as enhancing his ability to learn, but requested the yoga teacher taper off instructions as the intervention continued.

As we’re going through it she [the yoga teacher] tells us the next step so that we can follow it, and then we go repeat it multiple times, which helps us learn it for sure, but maybe she should - toward the end of that - she should start just cueing us but not quite as much so we can learn to do it.

3.4 Final Reflection of Experiences: Comfort Facilitates Benefits

Following the completion of the intervention, participants reflected on their experiences in a final focus group and individual interviews. Participants’ described a continuation and growth of the experiences discussed in the mid-way focus group, ultimately leading to benefits including physical changes, cognitive awareness, and emotional connection. As Gi explained in his individual interview, the intervention experience affected him on a holistic level, impacting both mind and body.

Completely changed. It’s helped me – both [my wife] and I say it’s helped me with my balance and my confidence. It’s helped me with my pain, mentally, emotionally, physically inside, you know? I can slow down and just focus on the good things and relax.

Physical changes through body balance and relaxation. Several participants described a continuation of physical comfort facilitated by the yoga teacher’s use of pose modification to create physical ease. For some, this continuation led to improvements in ability. Cari described her ability to complete the eye exercises in the second half of the intervention, which she attributed to overall health improvement and progressing from doing exercises in a seated position to lying supine.

At the beginning of the class I couldn’t do the eye exercises at all. The second half at least a couple times when we were doing the lying down, I could do the eye exercise…I am honestly not sure how much of it was the fact that we were actually laying down, that might have played into it or, I don’t know. I’ve felt just better health-wise in general, so I don’t know if that’s part of it too.

Several participants described having physical pain before coming to yoga, and feeling alleviation or decrease in their pain by end of the class.

Cari: There would be times I’d wake up in pain and laying on the heat pad and everything, but I’d still be in pain when I went to yoga, and then after yoga, I’d be feeling so much better, so it helped in that regard. I feel more relaxed, yet I’d have energy.

Gi: When I got here I had a really, really, really, really, really, really-I’m sorry, but it was a really bad headache…It was just burning this morning. I almost didn’t come. I was just hurting. I felt real off balance, but, you know, I feel pretty good right now.

Physical changes were not consistent across all participants. Erin described feeling more pain in her shoulder, knee, and groin during the second half of the intervention due to changing positions from seated, standing, and lying supine. She described how the experience affected her plan to continue practicing yoga, “I’m going to try it [yoga] on my own like the standing things, but I am not going to get down on the floor again cause it just takes…ugh.”

Cognitive awareness through scanning the body. Ann and Gi spoke about changes in their perception of pain. Instead of simply registering pain, they focused on becoming cognitively aware of the source and cause of their pain.

Ann: I think it’s gone deeper like instead of just, ‘this hurts,’ I think it’s kind of deeper like, ‘where is that coming from?’ kind of thing.

Gi: My thought process is - where am I hurting? …I think that the yoga has changed my thought process a little bit just because that’s what she [yoga teacher] was teaching…Take your time. Think about what you’re doing. Find out how your body’s feeling and stuff like that, and that was something that…I didn’t do on a regular basis and I do much more of now than I used to.

The yoga teacher guided participants through a ‘body scan’ towards the end of each yoga session, a series of verbal instructions to bring attention to the relaxation of individual body parts while in supine. Many participants described experiencing increased body awareness through the use of this strategy.

Cari: When she’s [yoga teacher’s] doing the body scan, it reminds me for some reason I always am pushing my tongue up against the roof of my mouth…and the fact that she says ‘relax your tongue,’ and I’m like, ‘oh, it’s not relaxed again’…so it helps because she made me aware of that, even outside of yoga.

Emotional connection through supporting each other. Many participants reflected on feeling an emotional connection among their peers within the intervention and with the yoga teacher. Gi exemplified the experience of connection stating, “this group is just nice to communicate and be in the fellowship of you guys being in my yoga class, where you guys understand.” Participants described feeling supported and encouraged by one another. This theme is best exemplified in the following exchange that occurred during the focus group as a response to Bill’s expression of frustration regarding regaining strength in his recovery.

Bill: I was in good shape.

Ann: But that’s not your value. It is not your value.

Cari: Yes. Your value is you, not what you’re pressing, not what you’re walking. You’re your own value and you have to accept you’re different, but that doesn’t mean you have to stay in this spot. You are different and you can progress from here.

Ann: And just because you’re different doesn’t mean you’re not as good.

Gi: [Bill], I’m not going to talk down to you. I’m not going to give you advice. I’m not going to tell you how to feel or not feel. [Takes deep inhale] I am…

Group response: Strong!

In an offering of support, Gi led his fellow participants in reciting an affirmation used throughout the yoga intervention (“I am strong!”). The participants’ commonalities of experiencing and understanding TBI and participating in yoga together created a connection that resulted in emotional support.

3.5 Impact on Daily Life Occupations

As participants progressed through the yoga intervention, they described ways in which their experiences affected occupations outside of the intervention. Participants described yoga influencing health maintenance and social interaction.

Body and breath awareness helps health maintenance and sleep. Participants Dan and Gi both described increased body awareness. Dan described an increase in his ability to pay attention to his body’s signals while working on the computer as a result of learning body awareness in yoga. For Gi, body awareness, or the idea of sensing and realizing how his body feels, led to understanding his body’s capacity, which helped with balance and fall avoidance at home.

Now I sit up in bed, and I take notice of where I am and what is hurting…and I can stretch and move and sometimes I can stand up and just reach for the door handle. I’m not worried about wobbling or stuff like that. She [yoga teacher] has helped me to take that notice of where that knot was or concentrate and just hold it. Just hold it, and stretch it a little bit, and just get it out of there, and then when I stand up I’m not losing my balance because I’ve got a knot in my back.

Similarly, both Cari and Ann felt their increased body awareness aided in health maintenance at home when experiencing health challenges. Cari occasionally experiences “episodes” which she described as intense nausea, dizziness, and headaches. She described how knowledge of her body’s capacity led to avoidance of such an episode.

Then on that Thursday as soon as I started to feel that [episode coming on], I was like I’m done. I walked away from the jigsaw puzzle and came in here and just, I just relaxed, ate something, and chilled for a little bit and it didn’t go into a full blown episode for me…It’s [yoga’s] helped me be a little bit more focused on my body and realize some things that I could do to help prevent an episode coming and stuff, so yeah, it’s been definitely helpful.

Ann is prone to seizures and in the second month of the yoga intervention while she was at home, had three seizures within 24 hours. She described the impact of practicing yoga on her recovery:

I think I had more health problems the second half [of the yoga class], cause I had a couple falls and I started having large seizures, but I think I recovered from them faster with the yoga than I would have without it.

Participants described using breath work including focusing on breathing and aligning breathing with movement in their daily life activities, to decrease overwhelming feelings of stress and to aid in sleep/wake cycles. Bill described using ujjayi breathing, a technique taught by the yoga teacher, to transition to sleep. Ujjayi breathing involves diaphragmatic breathing with a constriction of the throat, which Bill playfully referred to as the “Luigi” breath.

I can at least breathe through my nose. And I use it at night when I go to sleep. I use it to help me go to sleep. I tell [the yoga teacher] I go to my Luigi breath. That’s the breath that makes noise.

Ann described using the breathing techniques in the morning to aid in waking:

When I get up in the morning, the first thing I do now is take some deep breaths and stretch, and that wakes me up, whereas before, I don’t think I was doing that, and I think that I was foggier longer, and it took me longer to wake up.

Use of yoga techniques in other therapy. Dan and Cari reported incorporating techniques they learned during the yoga intervention into other therapy attended during their recovery. Dan described his incorporation of yoga techniques into trigger point therapy:

You start kind of in the stretch, you know, trying to figure out how to incorporate the - let’s just call it the flow - that we had in class, to those stretches. It’s a whole lot more fun.

Cari reported an increased capacity to perform exercises in physical therapy as a result of techniques she learned in the yoga intervention:

Some of my physical therapy and some of my vision therapy things were both incorporated in this yoga, which I found really interesting and so, it helped me figure out how to do the physical therapy ones, which I’d been having difficulty figuring out a way that I could do it.

Increased confidence in walking. Bill, Ann, and Gi described increased confidence in balancing and walking after participation in the yoga intervention. Bill reported, “I think I’m – what’s the word? – more confident in the things that I do, exercising and walking and stuff.” Similarly, Gi spoke of increased confidence in balancing and walking throughout his daily routine. Ann described a change in her perspective of her abilities:

I was focusing a lot on what I can’t do, and I think with the yoga I was more feeling empowered with what I can do, and realizing that um my body hasn’t totally given up on me.

Social interaction leads to social participation beyond intervention. All participants expressed experiencing increased social interaction as a result of the group yoga intervention. For some, friendships developed that extended beyond the yoga class. Fiona spoke of her relationship with Erin: “she showed me a side of myself that I didn’t know really existed, and I was like-it was amazing! …It’s amazing what one connection can do.” Erin did not have a vehicle to drive to the yoga classes and expressed interest in carpooling with other participants. Fiona began giving Erin rides and the two formed a friendship.

So, you know I was more than happy to help out whenever I could and she did a lot for me, and she was very inspirational for me and, our conversations, you know, days that were bad and she just has that sense of humor.

Fiona described her social interaction with Erin impacting her perception of relationships on a broader scale:

I learned that it’s not so scary to get to know someone, even if they’re not like me on the surface…I know that there’s been times when I’ve wanted to do certain things, and I shy away from ‘em if it’s with other people. So that was another lesson, like something I learned about myself, you know? That I’m - I know I’m not alone, but to really know I’m not alone, you know? There’s a difference from – between when the head stuff goes to your heart.

Connections initiated through the yoga intervention often developed into social interactions outside of the intervention. Erin spoke of Dan’s offer to help her set up her home computer, and Bill described giving Dan rides from the bus stop to the laboratory. Cari described creating a new, shared occupation with her caregiver as a result of attending the yoga intervention together:

Almost every day after yoga, [my caregiver] and I would go for a walk for an hour…and that was part of what was, you know, it was just great! We’d have yoga. We’d get all loosened up and, you know, made it so that we were ready to walk.

4. Discussion

This study provides an initial understanding of the experiences of engaging in a group adapted yoga intervention from the perspective of individuals with chronic TBI. Based on the interpretation of the reoccurring experiences voiced by the seven participants, we identified three major inferences. First, it appears that the experience of physical, emotional, and cognitive benefits occurred secondary to the establishment of a safe and comfortable environment. Second, despite beginning expectations of experiencing only physical benefits from yoga, participants describe perceptions of benefits on a more holistic level with improvements expanding to emotional and cognitive aspects as well. Finally, it seems that learned yoga techniques and social interactions experienced during the yoga sessions affected daily occupations or activities outside of the intervention.

Participants from this study described perceptions of beneficial effects from yoga occurring with the preliminary establishment of a safe environment. This has important implications for the structure of future studies in the same research area, as this was the first study to record qualitative data midway through a yoga intervention. Prior to experiencing the benefits described during the final focus group and interviews, participants in this study described feelings of physical, emotional, and cognitive comfort within the environment where the yoga intervention occurred during the midway focus group. Feelings of comfort and safety were described as resulting from the existence of commonalities among fellow participants, including having a TBI and belonging to the same support group. In this study, creation of a safe environment occurred through the intentional use of inclusion criteria of having the same diagnosis (chronic TBI) and the unintentional recruitment from a single TBI support group. An additional intentional strategy was the use of a yoga teacher who is also an OTR/L. The OT therefore possesses the knowledge of adaptation and modification of the physical environment to fit the needs of individuals with TBI.

Disability and rehabilitation literature supports similar inferences for individuals with other neurologic disorders and disabilities in general [13,30]. Garrett, Immink [13] evaluated the effects of a ten-week yoga program for people with stroke. Participants described how the environment of the intervention affected their ability to experience outcomes. For example, participants in Garrett’s study described an environment in which they felt safe knowing the yoga teacher had knowledge of their physical and cognitive limitations, and they felt no pressure or judgment of their abilities and were encouraged to stop if they felt pain. Such descriptions align with the findings in the current study of the significant role of safety in promoting therapeutic change, whether it is physical, emotional, or cognitive. Hammel, Magasi [30], qualitatively explored the meaning of participation for individuals with disabilities, and their results further support the importance of safety and security in eliciting change. Participants in the study by Hammel, Magasi [30] described active engagement in all daily life activities as being contingent on feelings of personal security within the social environment. This finding directly supports the finding in the current study, that therapeutic changes during the yoga intervention were predicated upon participants feeling socially and physically safe within the intervention environment.

The physical, emotional, and cognitive benefits of yoga for individuals with TBI is supported by prior clinical research of yoga for individuals with brain injuries [16,17,19,20]. Additionally, limited qualitative data from yoga research for individuals with brain injuries supports the inference of increased participation in daily life activities in congruence with practicing yoga [8,16].

Future studies may also seek to determine if there is any correlation between the experience of participation in a yoga intervention and mechanism of injury. There were differences in outcomes and expectations between participants with various types of brain injuries in this study, however due to the small sample size, it is difficult to indicate if these differences are a reflection of each participants individuality or are influenced by mechanism of injury. The influence upon experience based on mechanism of injury is an important avenue of study, which would provide further insight into the experience of yoga for individuals with TBI.

4.1 Clinical Implications

Figure 1 illustrates the participants’ experience of the yoga intervention and indicates the dynamic process of the experience as the yoga intervention progressed. This model illustrates the importance of implementing intentional strategies when designing yoga interventions to increase the likelihood of physical, emotional, and cognitive outcomes. Based on the results of this study, these strategies helped to create a physically, cognitively, and emotionally safe environment. Practitioners designing an adapted group yoga intervention for individuals with TBI might consider implementing similar strategies. Strategies may include: inclusion of similar participants; having a yoga teacher with knowledge in adaptation of the environment through dual practice in yoga and OT; re-conceptualization of yoga as pain free and non-competitive; and use of yoga principles including breath through movement and body scanning to facilitate relaxation and body awareness.

Additionally, yoga appears to be beneficial to individuals with TBI by impacting physical, emotional, and cognitive domains. Because cognitive and psychosocial deficits persist or appear as secondary problems later in the TBI disease process, yoga may be a valuable option for individuals in the chronic stage of TBI recovery [3,4,15]. Finally, the results of this study coincide with recent literature acknowledging the functional benefits gained through the use of complementary integrative health approaches in rehabilitation for individuals with TBI [31].

4.2 Strengths and limitations

The use of multiple validation strategies [25], implemented throughout the data collection and analysis processes, strengthened the rigor of this study. The primary author maintained prolonged engagement and persistent observation in the field by observing all yoga sessions, conducting all interviews and focus groups, and transcribing verbatim all audio recordings. The triangulating analyst provided an external check of the research process and kept the first author authentic in methods and meanings ascribed to the data. Creswell [25] recommends using at least two validation strategies, and the use of multiple strategies indicates the high degree of rigor observed by the authors, strengthening the study results.

While the emphasis of studying the experiences of one small group intensely over time is a strength of the qualitative paradigm in this phenomenology, this study’s small sample size limits the possibility of applying findings to a larger population. Another potential limitation of this study is the timing related to the collection of data on the study participants’ initial expectations of the intervention outcomes. Participants were asked to reflect on their expectations for the yoga sessions retrospectively, during their final individual interview. By this time the experience of engaging in the intervention could have affected how they expressed their initial expectations. Asking participants to explain their expectations before the beginning of the intervention would have strengthened this portion of the study’s data.

Furthermore, it cannot be concluded that the participants experienced therapeutic changes solely because of yoga or the safe environment created by the commonalities among participants. For example, benefits could have occurred simply because the intervention required participants to leave their homes twice a week and navigate their way to the research lab for yoga class. The qualitative data collection process also required them to reflect upon their experience through narrative storytelling during individual interviews and focus groups. These elements of the intervention require physical, emotional, and cognitive engagement not directly linked to the activity of practicing yoga, but are possible reasons for experiencing therapeutic benefits. There was not a control group for this pilot study, so it is impossible to know the specific effects of yoga alone.

Additionally, the primary researcher transcribed both focus groups solely and therefore interjudge reliability of transcriptions was not utilized. Moreover, while the primary researcher was present for both focus groups, she did not complete transcription during the live event and therefore intrajudge reliability of transcriptions was not utilized. These limitations decrease the reliability of the transcription data.

Finally, while several validation strategies were used to increase rigor, member checking, or the process of soliciting participants’ views of the credibility of the findings and interpretations [25] was not employed. While member checking would have increased the credibility of the study, contact with the participants beyond the final interviews was not stipulated in the original IRB proposal, and data analysis took place several months after data collection. Therefore, aside from the IRB barrier to performing member checks, it was determined by the researchers that member checking accuracy would be difficult considering participant self-reported memory problems and the elapsed time since the intervention. Despite not member checking, we nevertheless found tremendous overlap between the statements made by the participants in the focus groups and in their individual interviews. This consistency of reporting by the participants substantiates the accuracy of the findings of this study, which may offset the inability to perform member checks.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study provides important insights regarding the experiences of individuals with TBI in engaging in an adapted yoga intervention. The implications of these experiences can be used to inspire future research exploring the benefits of yoga for this population. Possible future research might include a randomized comparison trial with a large sample size comparing yoga to a different intervention. The comparison group in a yoga study of this kind will need to control for important aspects of the intervention. Examples of controlled aspects for both the yoga and control group might include: attending the same amount of sessions in the same physical environment; being taught by an interventionist who is also a therapist; spending the same amount time with the therapist; and having similar group sizes. It may also be helpful to incorporate a mixed-methods design comparing the outcomes of a group in which both quantitative data and qualitative measures are taken with those of a group in which only quantitative measures are taken. A study of this kind could explore the possibility of the influence of the narrative method on therapeutic outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The individuals with chronic TBI in this study experienced the adapted yoga intervention as a process. Prior to beginning the study, they expected physical benefits from yoga. Halfway through the intervention they experienced feelings of safety and comfort within the intervention environment. Finally, their experiences of comfort and safety led to physical, emotional, and cognitive changes. Participants also described how these changes affected aspects of their daily life including health maintenance and social participation. This study provides insight into how an adapted group yoga intervention was experienced by a group of individuals with chronic TBI. The results support recent literature acknowledging the functional benefits gained through the use of complementary integrative health approaches for individuals with TBI [31]. Additionally, the participants provided evidence of the importance of establishing a safe and secure intervention environment in promoting desired outcomes. The positive outcomes experienced by participants indicate the need for further study of adapted group yoga as a possible intervention strategy for individuals with chronic TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the intervention participants for sharing their stories and providing the invaluable insights that built this study. The authors also acknowledge the dedication and effort of the study’s yoga teacher and OTR/L, Katelyn Knox. Finally the authors would like to thank the Colorado State University College of Health and Human Sciences for generously providing funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Schmid and Roney were involved in the intervention. Roney and Sample were involved in data collection and development of focus groups questions. Roney and Sample were involved in qualitative data analyses. All authors were involved in writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported through funding from the Colorado State University College of Health and Human Sciences.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to congress on tramatic brain injury in the United States: Epidemiology and rehabilitation. Atlanta, GA: 2015.

- Conti GE. Acquired Brain Injury. In: Atchinson BJ, Dirette DK, editors. Conditions in Occupational Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. p. 179-198.

- Andelic N, Sigurdardottir S, Schanke A-K, Sandvik L, Sveen U, Roe C. Disability, physical health and mental health 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010; 32: 1122-1131. [CrossRef]

- Geurtsen GJ, van Heugten CM, Martina JD, Geurts AC. Comprehensive rehabilitation programmes in the chronic phase after severe brain injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2010; 42: 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Haggstrom A, Lund ML. The complexity of participation in daily life: a qualitative study of the experiences of persons with acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2008; 40: 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Colantonio A. Effectiveness of rehabilitation in enhancing community integration after acute traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2010; 64: 709-719. [CrossRef]

- Levack WM, Kayes NM, Fadyl JK. Experience of recovery and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 986-999. [CrossRef]

- Gerber GJ, Gargaro J. Participation in a social and recreational day programme increases community integration and reduces family burden of persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2015; 29: 722-729. [CrossRef]

- Stephens JA, Williamson KNC, Berryhill ME. Cognitive rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: A reference for occupational therapists. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2015; 35: 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Bayley-Veloso R, & Salmon, P.G. Yoga in clinical practice. Mindfulness. 2015: 1-12.

- Smith JA, Creer, T., Sheets, T., & Watson, S. Is there more to yoga than exercise? Altern Ther Health Med. 2011; 17: 22-29.

- Van Puymbroeck M, Miller KK, Dickes LA, Schmid AA. Perceptions of yoga therapy embedded in two inpatient rehabilitation hospitals: agency perspectives. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015; 2015: 125969. [CrossRef]

- Garrett R, Immink MA, Hillier S. Becoming connected: the lived experience of yoga participation after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 33: 2404-2415. [CrossRef]

- Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010; 16: 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Cantor JB, Gumber S. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in treating individuals with traumatic brain injury. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013; 1: 159-168. [CrossRef]

- Schmid A, Miller K, Van Puymbroeck M, Schalk N. Feasibility and results of a case study of yoga to improve physical functioning in people with chronic traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2016; 38: 914-920. [CrossRef]

- Johansson B, Bjuhr H, Ronnback L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) improves long-term mental fatigue after stroke or traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2012; 26: 1621-1628. [CrossRef]

- Johansson B, Bjuhr H, Rönnbäck L. Evaluation of an advanced mindfulness program following a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program for participants suffering from mental fatigue after acquired brain injury. Mindfulness. 2015; 6: 227-233. [CrossRef]

- Silverthorne C, Khalsa SBS, Gueth R, DeAvilla N, Pansini J. Respiratory, physical, and psychological benefits of breath-focused yoga for adults with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI): a brief pilot study report. Int J Yoga Therap. 2012: 47-51.

- Donnelly KZ, Linnea K, Grant DA, Lichtenstein J. The feasibility and impact of a yoga pilot programme on the quality-of-life of adults with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017; 31: 208-214. [CrossRef]

- Schmid A, Miller K, Van Puymbroeck M, Schalk N. Feasibility and results of a case study of yoga to improve physical functioning in people with chronic traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2015; 38: 914-920. [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz K, Howie L, Lentin P. Client-centred practice: Perspectives of persons with a traumatic brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016; 23: 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Darragh AR, Sample PL, Krieger SR. Tears in my eyes, ‘cause somebody finally understood’: Perceptions of care providers by survivors of brain injury. Am J Occup Ther. 2001; 55: 191-199. [CrossRef]

- Yost TL, Taylor AG. Qigong as a novel intervention for service members with mild traumatic brain injury. Explore (NY). 2013; 9: 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Stoller CC, Greuel JH, Cimini LS, Fowler MS, Koomar JA. Effects of sensory-enhanced yoga on symptoms of combat stress in deployed military personnel. Am J Occup Ther. 2011; 66: 59-68. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham A. Stretch & surrender: A guide to yoga, health, and relaxation for people in recovery. 2nd ed. Portland: Rudra Press; 1992.

- Roney MA, Sample PL. Final focus group agenda. Unpublished focus group guide. 2016.

- Roney MA, Sample PL. Mid-way focus group agenda. Unpublished focus group guide. 2016.

- Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Whiteneck G, Bogner J, Rodriguez E. What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2008; 30: 1445-1460. [CrossRef]

- Hardison ME, Roll SC. Mindfulness interventions in physical rehabilitation: A scoping review. Am J Occup Ther. 2016; 70: 7003290030p1-7003290030p9.